INTERVIEW: Filmmakers Behind Doc ‘Ayahku, Dr. G’ Discuss Legalising Cannabis & Meeting Dr. Ganja

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

For avid readers of JUICE, it will come as no surprise that we have written multiple stories revolving around the subject of marijuana. From covering a strong advocate for cannabis use within the Malaysian royal family, to extensively detailing the origin of Malaysia’s War On Drugs, we believe that education is the key to understanding the plant and finally drawing that line in the sand.

Distinguishing benefits from stigma is vital in the path towards legalising or decriminalising the herb and what better figure to be at the forefront of this conversation than Dr. Ganja himself?

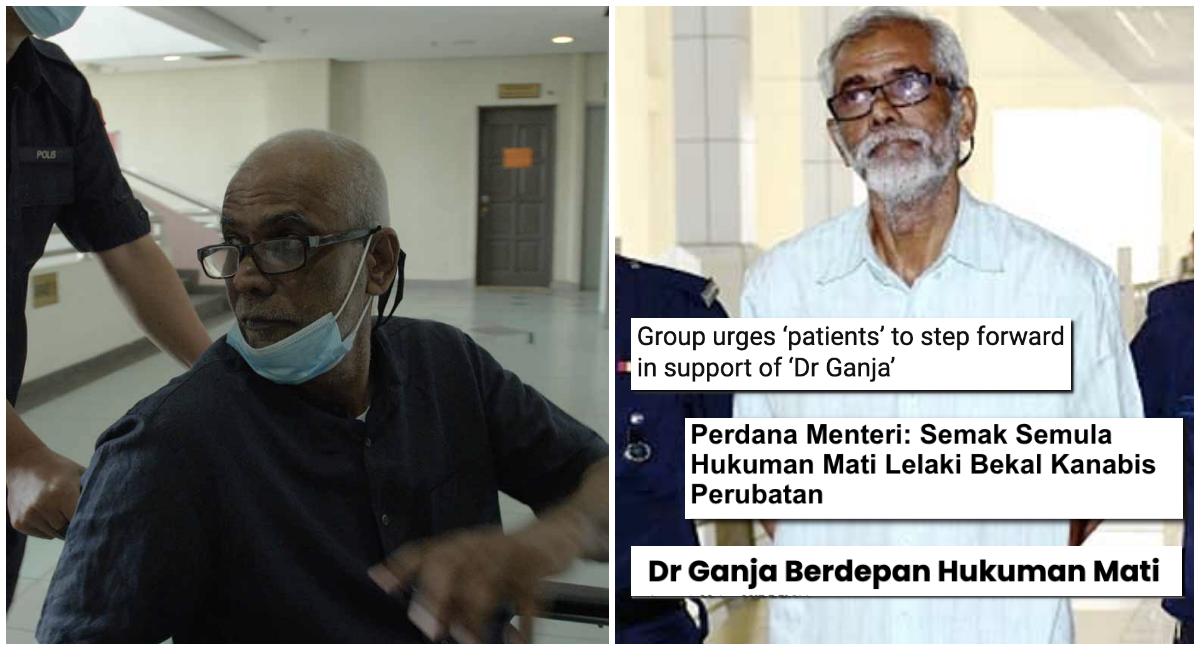

For the uninitiated, Dr. Ganja @ Amiruddin Nadarajan Abdullah is a military retiree who ailed his illness as well as helped others through bouts of epilepsy and leukemia by using cannabis. In 2017, he was arrested for 36 counts of drug-related offences under the Dangerous Drugs Act in Malaysia and faces the mandatory death penalty if found guilty.

His story was plastered on newspapers and his name was bolded in all the headlines. Painted as a criminal rather than a healer, Dr. Ganja’s real story was overshadowed by buzz and speculation from the media. Instead of lending our ears to listen to actual details of the case, Malaysians muted him and amplified our own uninformed criticisms towards his actions.

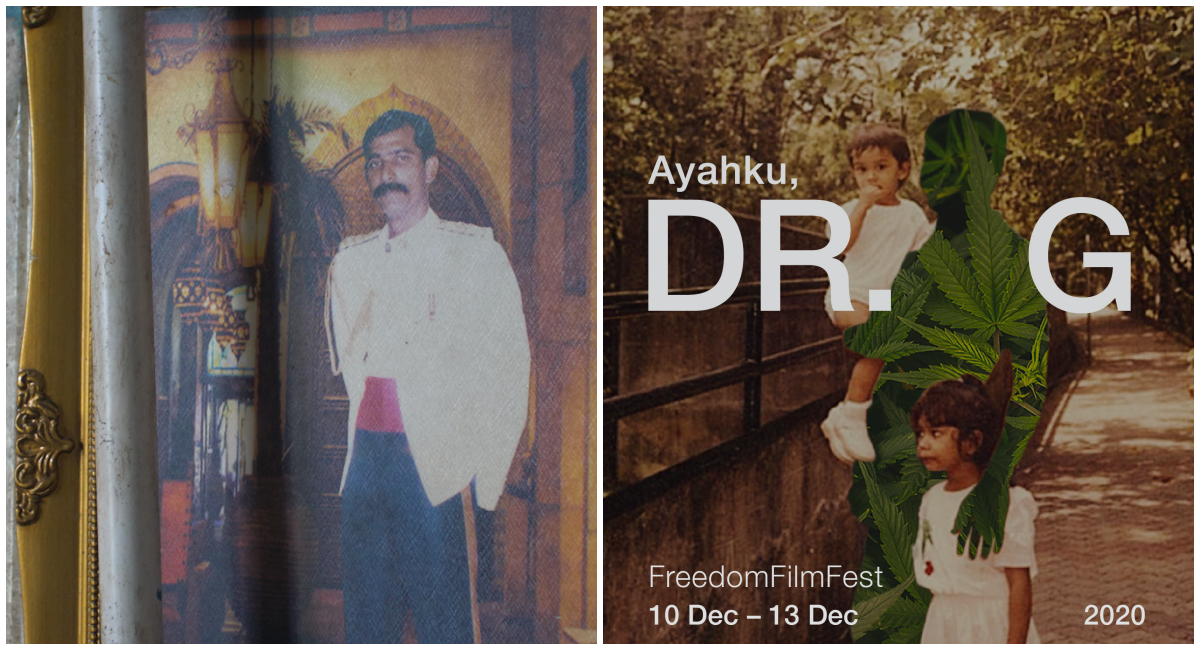

Now, a group of young filmmakers are determined to set the record straight through a documentary which was filmed within the lens of Dr. Ganja’s own daughter, Siti, aptly titled, Ayahku, Dr. G.

At the centre of unrelenting legal proceedings and prison visits after her father’s arrest, Siti’s battle for the destigmatisation of drugs in Malaysia as well as her own bouts of fear and anxiety doesn’t come without a few personal challenges. Heightened by the looming thought that she may never see her father again, Ayahku, Dr. G holds a tight grasp on Siti as much as it does on the audience.

We at JUICE were lucky enough to have chat with the filmmakers behind the documentary that will be premiering at Freedom Film Fest on 10 December and 12 December. Introducing the voices of Loh Jo Yee (JY), Hidayah Hisham (HH) and Dominique Teoh (DT), here is our interview with the brave minds behind Ayahku, Dr. G…

What drew you into making a film about Dr. Ganja?

JY: When I first came across the news of Dr. G in 2017, he first struck me as an Asian Clint Eastwood from the spread of media coverage with his face sprawled all over the headlines. His smile, even in the face of adversity, showed no defeat, only a sense of revel in courage and even strength in the known or unknown. Being a video producer, Dr. G’s story immediately tingled my spidey senses that this was no ordinary story. Everything from his background to his personality was incredible even on its own, and the story about Dr. G felt almost like a communal open secret across a spectrum of cannabis advocates and consumers.

HH: If our country were to ever benefit from the success of cannabis in the future, the documentation of Dr. G’s discrimination is an important reminder of what it took for us to get there. I was aware of the challenges of tackling a complicated subject, but Dr. G’s truth deserves to be heard.

DT: I learned a lot about the U.S criminal justice system when I was studying there, but I didn’t know much about ours. Dr. Ganja’s story highlights so many issues that we need to address — that not everyone who is arrested on drug charges is desperate for a high, many are desperate for a cure; that you can spend years in prison without having been found guilty; and that our laws don’t just punish the accused, but also their families.

What was the hardest thing about tackling a topic as polarising as marijuana use in Malaysia?

JY: The hardest thing about tackling a topic like this is that the fine line between what is right and wrong can sometimes appear very muddled especially when it relates to a topic that has been in the grey. Our local perspective views towards cannabis usage is almost as outdated as the act itself that dates back to 1952.

HH: I think getting all the facts right was a huge difficulty, we anticipated many criticisms and doubts over the topic of using marijuana for medicine, we wanted to be prepared to contradict those opinions by being as factual and objective as we can. There’s still so many things we don’t know to this conversation (in terms of Malaysia’s laws and policies), we really had our work cut out for us in that part – we still don’t have the full picture but one thing is clear to us despite the mixed views people have towards our subject – our laws don’t protect enough when our marginalised communities are overrepresented on death row.

Walk us through a typical day on set.

JY: Our filming periods would often be a stretch of days usually centred around the court hearing dates for Dr. G and with very little rest and sleep in between, we try to document or even spend as much time as we could with Siti and other family members of Dr. G to immerse ourselves into their worlds. This would often lead to us spending many meals and moments with the people surrounding the subjects of our film, and as a little treat, we would have downtime and relax after these intense filming periods.

HH: We would normally start as early as 5am on the day of the shoot. We would prep our gears the night before so we could head straight to wherever Siti is on that day. Since Siti starts her day as early as 4:30am to prepare for her long journey to visit her dad in Sg Buloh prison and in Shah Alam court, we are usually with her throughout most of the day until she finishes everything she needs to manage with her dad. That being said, we don’t really have a fixed schedule – our only breaks are when court is in session or when she visits him in the visiting area in Sg Buloh (where cameras are not allowed) and we just get ready as soon as she comes out to film her reaction and thoughts.

Who are some of your directorial influences when it comes to structuring and filming your documentary?

HH: I was watching Cameraperson by Kirstin Johnson on repeat during our production and post-production period – because she spent most of her career as a cameraperson, she always struggled with the idea that her work is an aestheticisation of people’s struggles because filming non-fiction can get borderline exploitative. I always feared that when we were filming this, are we exploiting Siti’s struggles to tell a good story? But Kirstin Johnson has this insisting way of making her characters bright and empowered in the midst of these dark struggles, and that was my guide in navigating my interaction with Siti – with and without my camera.

Without seeing the film, I can already tell the story will be emotionally impactful. Were there times when you had to take a break from it all?

JY: The time when I had to take a break from it all was when the communication breakdown started to happen between the crew members as a result of long periods of filmmaking, it’s like our whole world revolved around the film and sometimes it makes you forget how to live a ‘normal’ life when you have been in that mode for an extended period of time. When it’s hard for me to appreciate the little things that used to give me joy e.g. cooking, interacting with my loved ones, I know it’s time for a pause.

HH: Because making a film is a non-stop effort, I felt like we were kind of trapped in this velocity to be at Siti’s pace constantly. I realised that somewhere towards the final shoots of our films, it doesn’t help anyone if I don’t step out or take my team away from this world for a moment or two. I made sure to isolate myself as much as I can after spending a week with Siti, because coming back to my reality after being in hers can be a weird transition. Taking it easy is an understatement, but non-fiction is hard because it’s reality!

How was it like meeting Siti and documenting her journey through emotionally-taxing legal proceedings and prison visits?

HH: One of the biggest events that happened to me this year (other than the pandemic) was meeting Siti. As a filmmaker, it struck me how much a person can do so much in a day but keep their fights hidden from plain sight – asking her to let us film those private moments of her coping with her dad’s absence was such a huge asking of us, I still can’t believe she’d let us. I’m grateful she did, because I learned a lot about myself in the process – not just as a filmmaker, but as a person too.

DT: People often have simplified ideas about how a person in difficulty should be, that they’re not truly struggling if they laugh or that they’re selfish if they take time for themselves. But “struggle” and “strength” look different from one person to another. It was really inspiring to get to know Siti, to see how she balances adversity with joy, her duty as a daughter with duty to self, trust in God’s plan with her determination to free her father.

Did you meet Dr. Ganja? If so, what did you speak to him about?

HH: The only times we were allowed to talk to him was at court because of the security restrictions so we didn’t have much time to get to know him. From the very limited time we had with him, I always find my interactions with him mostly being about books or conspiracy theories, he’s just another uncle from PJ. Really funny and solid dude.

JY: The first time I met him felt very emotional for me because after having followed his story since 2017 and many moments of self-doubt as a filmmaker struggling to make sense of the gravity of it all, meeting the subject of the story I’ve been chasing and hoping for, right before my eyes felt surreal. Most of the time we were there just listening to him as he persistently talked about his advocacy and his belief in this plant that changed his life.

DT: Dr. Ganja is such a lively, animated person. It’s hard to get a word in when you’re with him, but then again you just want to sit and listen. He reads everything from Reader’s Digest to the Quran and the Bible, so the topics are quite diverse. We might have to add JUICE to the list.

What was the biggest post-production struggle you had to face?

JY: With documenting real life stories, a lot of risks needed to be considered and assessed. Would these clips or sound bites possibly put Dr. G and Siti at risk? These are some of the questions that we continue to ask until today as it could change from one moment to another. Amiruddin’s ongoing trial at court and Siti’s identity were some of the concerns we had to keep in mind as we piece the film together because of the taboo that still continues to surround the topic of cannabis as personified through the Dangerous Drug Act 1952. Balancing facts with emotions and delivering it creatively definitely calls for all hands on the deck.

DT: This is such a multifaceted story. It covers legalisation and the death penalty; it tells Dr. Ganja’s story, but just as importantly, his daughter’s. As an editor, it was a challenge to balance all these points and determine which ones to focus on. I had to find a way to balance our director’s vision, Freedom Film Network’s feedback and legalities surrounding Dr. Ganja’s case. I don’t know if I achieved that, but I was lucky to have guidance from Lau Kek Huat, who is himself a seasoned director and editor. He was very patient and supportive throughout the process.

HH: As the director, watching all of our footage (and hardwork) move into a timeline wasn’t an easy transition. Before and during the filming stage, I thought that the story I had in my head was concrete – but then I later realized that’s just false assurance, the story grows the most during the editing process. I’m really grateful that more experienced editors like Dominique and Kek Huat came in on the editing process at the same time that I was letting go of these rough cuts, without the both of them I would have probably wandered off of a cliff – bringing the story down with me too.

Observing society today, do you think that the legalisation and destigmatisation of marijuana is approaching us soon?

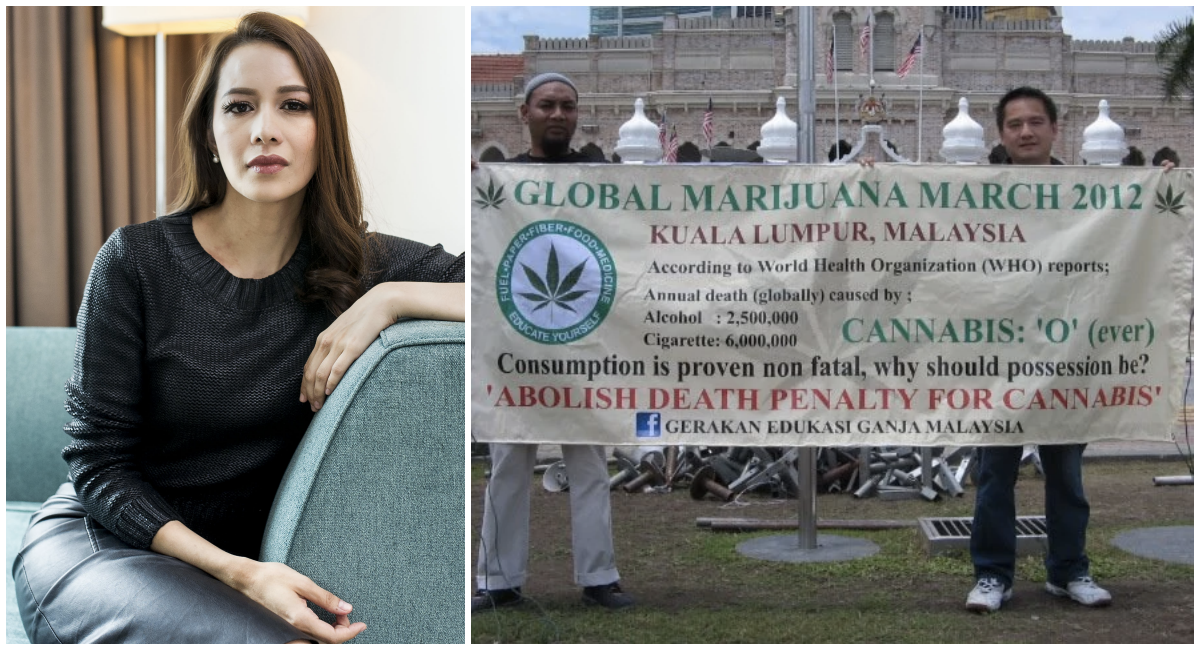

JY: I think public figures like Tengku Chanela for example help to normalise cannabis usage. Advocacy efforts today has the advantage of social media platforms and SEOs, and with more accounts of people discovering the benefits of medical cannabis for various treatments e.g. news about it being received so well amongst communities of users, we might actually have a shot at finally finding a solution to this war on drugs.

DT: I think the destigmatisation of marijuana is well in motion. So many people recognise its medical benefits, from medical experts to laypeople, orang bandar to orang kampung. That said, our harsh drug laws discourage people from speaking out. That’s one thing we’re hoping to do with this film — to push the conversation forward and normalise medical cannabis. In order to legalise, we need political will; to create political will, we need to put pressure on our leaders; and for that to happen, we need to destigmatise.

Do you feel that there is a lack of proper education regarding drug use in Malaysia that is not specifically targeted towards fear-mongering amongst youths?

JY: Definitely! I think with the support of our governments we can really achieve tremendous change in how we perceive cannabis consumption when we are not be occupied with fighting against one another. We can then find a solution that is inclusive of the many different layers in our society. And as our tagline goes, #KajiBukanKeji, we hope that reforms can be built upon something stronger than fear, which to me is a sense of duty we have towards protecting the people within our communities from harm and not from a place of fear as very little good can come out of that.

DT: We do need better drug education. Drug abuse is something that needs to be eradicated, but we need to reevaluate our approach to this problem. The death penalty hasn’t been an effective deterrent, and we’re punishing people with drug problems when what they need is support. We need to start treating drug abuse as a health issue and not a criminal issue — an approach that has been effective in reducing rates of relapse and recidivism. In this way, our society gets healthier. Drug users are as much a part of society as we are, so no one wins when we deny them the support they need or use them as boogeymen to scare our youth.

What was the most impactful moment in your documentary that you can’t wait for audiences to experience?

JY: Personally I think the phone calls were the most intimate and impactful bites that we got as there were direct phone calls from Dr. G while he was in prison to his daughter, Siti. Those were the only moments when we got to share a Dr. G himself with no barriers or walls in between. It’s challenging to make a film about a person when you could barely even spend any amount of time with them; however we hope that through his daughter’s eyes we get to see a different aspect of the burden carried by the people affected by this archaic law.

What is your goal with this film?

JY: Firstly, we want to educate or at least bring awareness to the multilateral effects of health and legal legislations by screening the documentary to a wide range of communities. These screenings and hopefully the conversations garnered from it would help to destigmatise discussions about cannabis use, and having our social media pages (@ayahkudrg on FB, Twitter & Instagram) up and running would make it easier for people who could then use it as a safe space to discuss cannabis and more after watching the film. Ultimately, we hope to bring together key agents from different associations to lobby for the decriminalisation of cannabis under the Dangerous Drug Act 1952 in parliament.

To get your tickets for Ayahku, Dr. G, click here.

To check out the other important films premiering at Freedom Film Festival, click here.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM