The Theory of Emo-lution

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Ah, emo music. You probably know of it as a joke of sorts; that one genre where everyone sings about being bullied in school and cries themselves to sleep at night. But like most things the internet makes fun of, there’s a lot more to the genre that goes unsaid and unheard. To help you decide once and for all if it’s truly golden or simply a garbage fire, we’re taking you on a comprehensive journey through the evolution of emo. So sit back, relax, and get ready for some new sides to the genre that you’ve possibly never seen before.

The ’80s: You Can’t Spell Screamo Without ‘Emo’

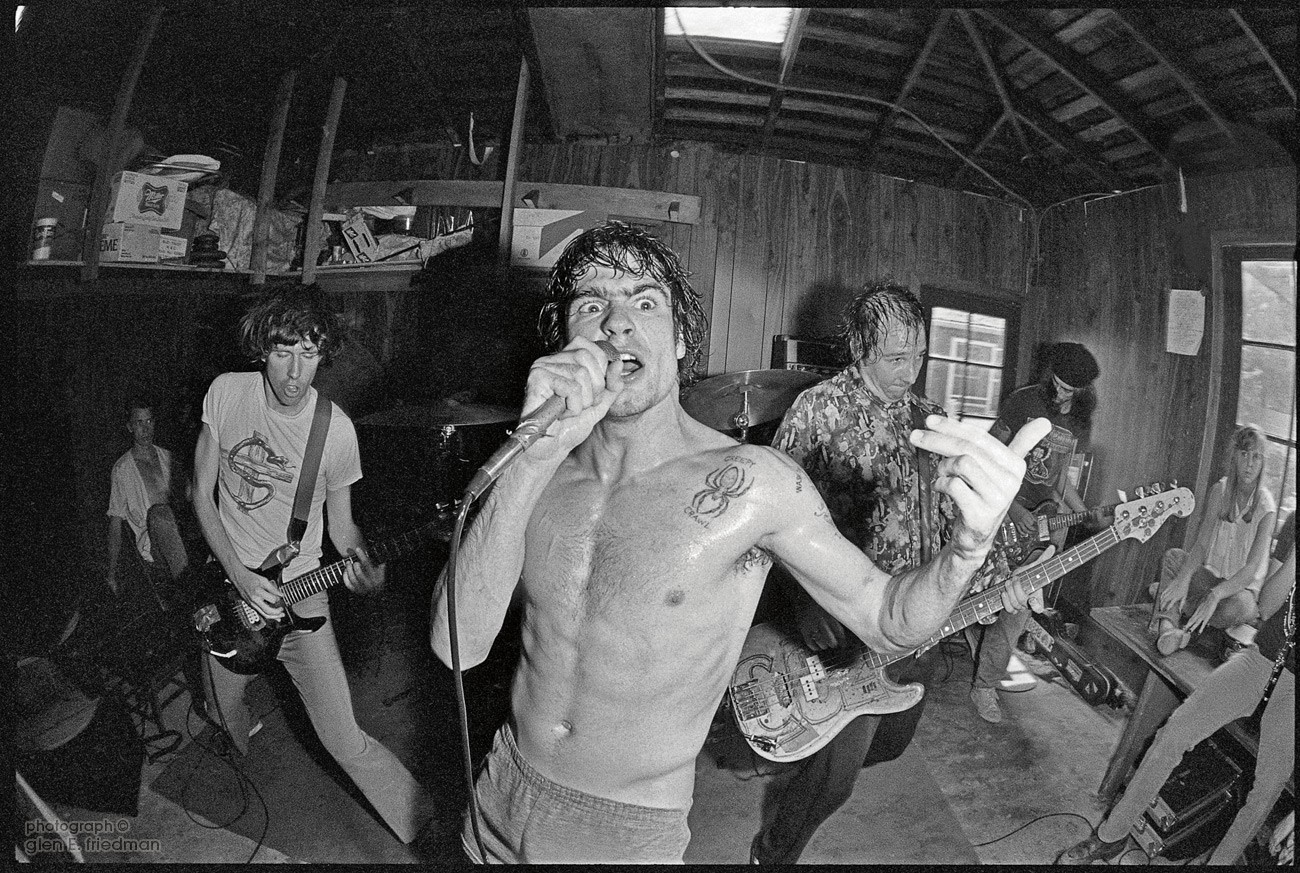

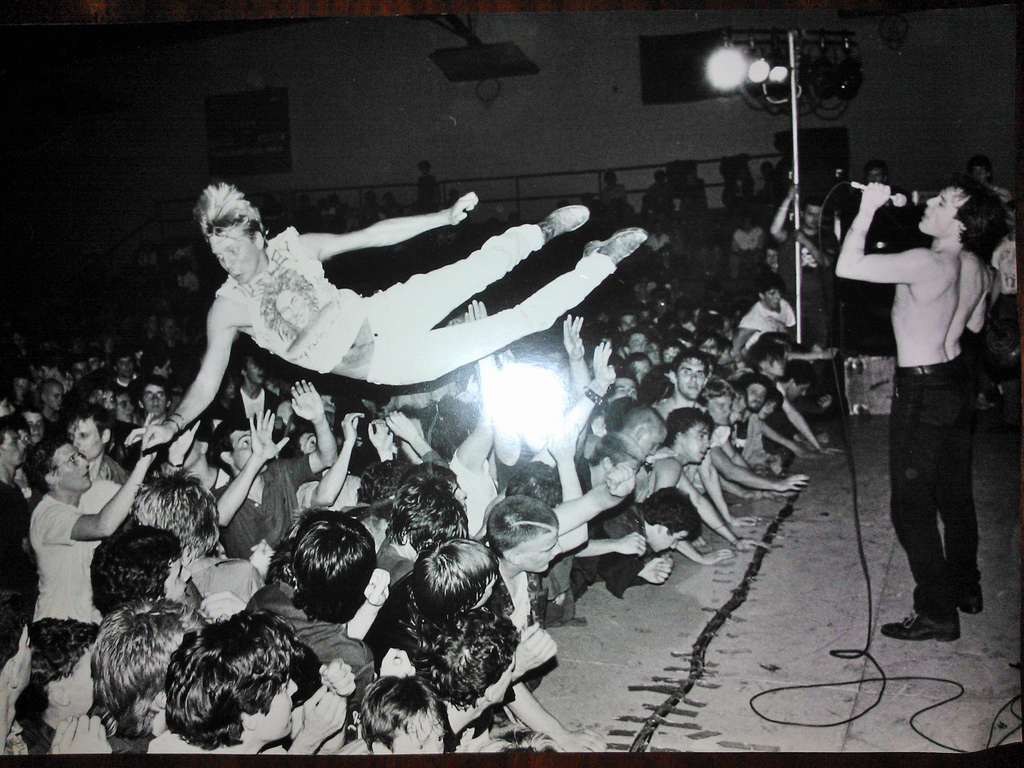

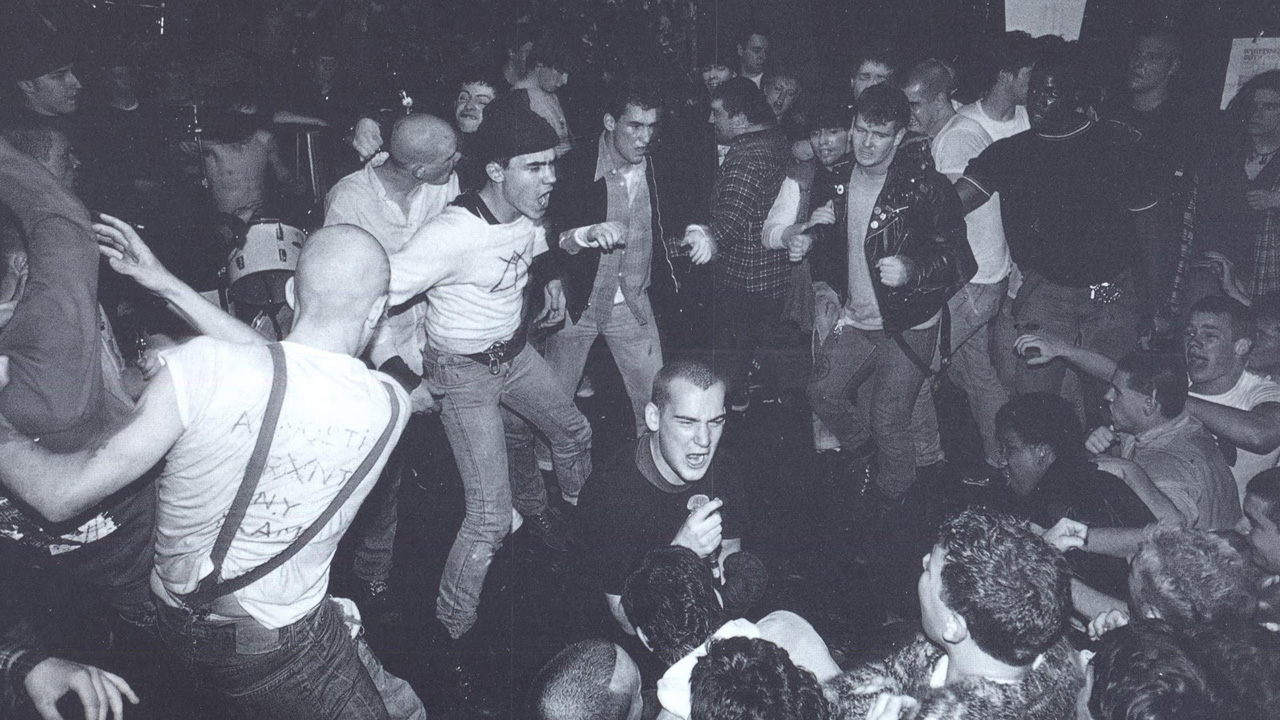

To truly understand how emo began, we must first take a journey back to a time when punk music ruled the hearts and minds of discerning music fans with good taste. Now, I’m not talking about the reggae-infused, fun, and funky vein of punk that swept the United Kingdom – I’m talking about its American cousin across the pond; loud, brash, and centred around destruction. Black Flag, The Dead Kennedys, and Hüsker Dü were just some of the famous names from this scene – famous for bringing guitar music into a realm just falling short of metal, inventing the moshpit, and channelling the collective anger of the American people. Granted, that description probably fits your idea of what “punk music” is – but not everyone was comfortable with this.

A small offshoot of American punk began around the mid-‘80s in response to the uncontrollable excess that was beginning to define the main brand of the genre. Known as ‘straight-edge’, this sub-genre was the antithesis to anarchical punk. It was embraced by bands who disavowed the ‘sex, drugs, and rock n’roll’ mindset, instead opting for complete sobriety, and sometimes even complete celibacy. The founding of straight-edge punk is mainly attributed to Ian MacKaye, frontman of hardcore punk band Minor Threat – as similar as their music was to the likes of Black Flag and the rest of the anarcho-punk cohort, their lifestyles were two worlds apart.

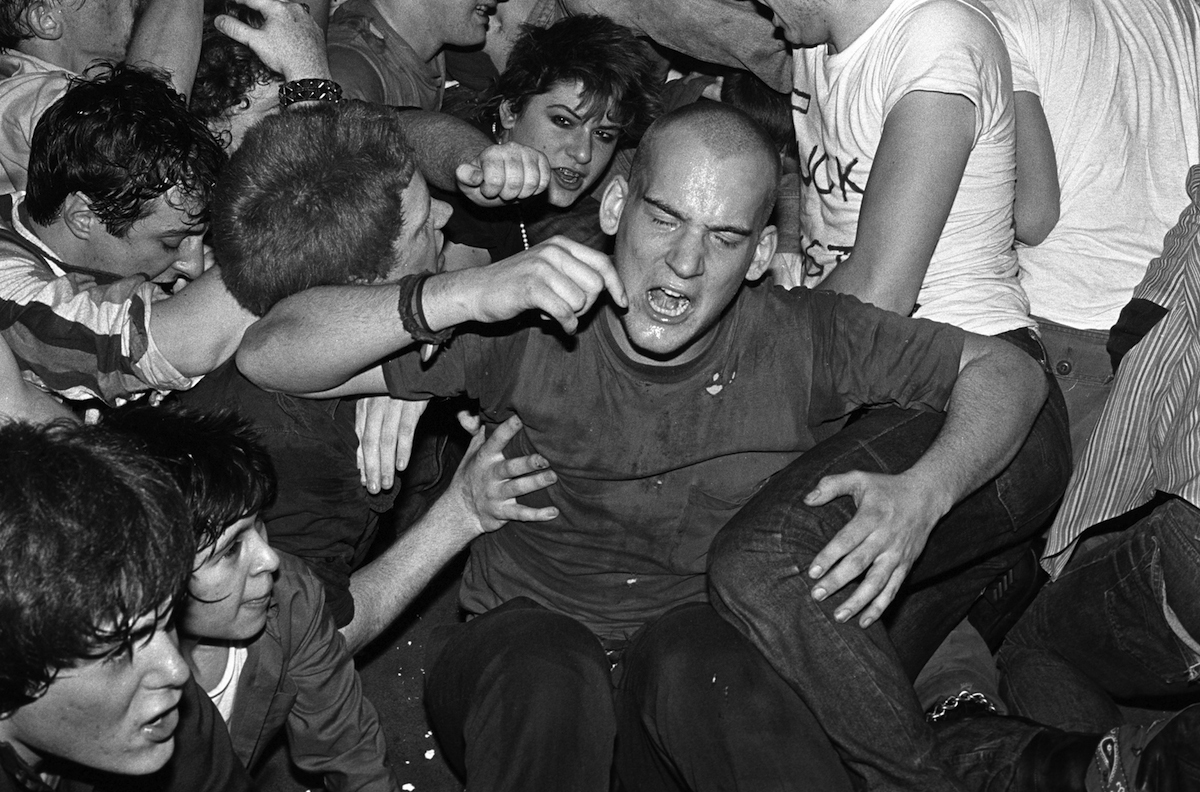

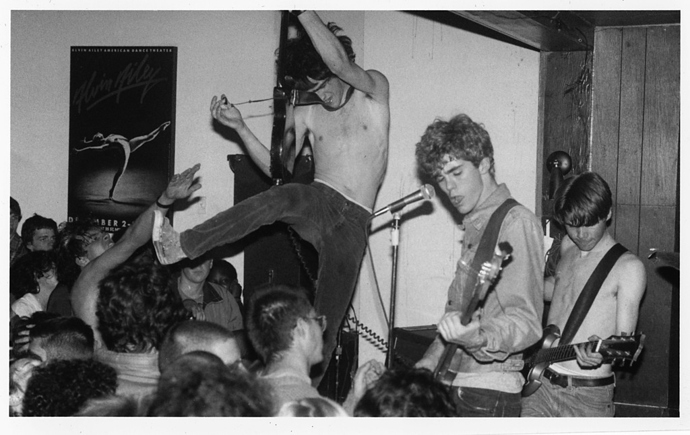

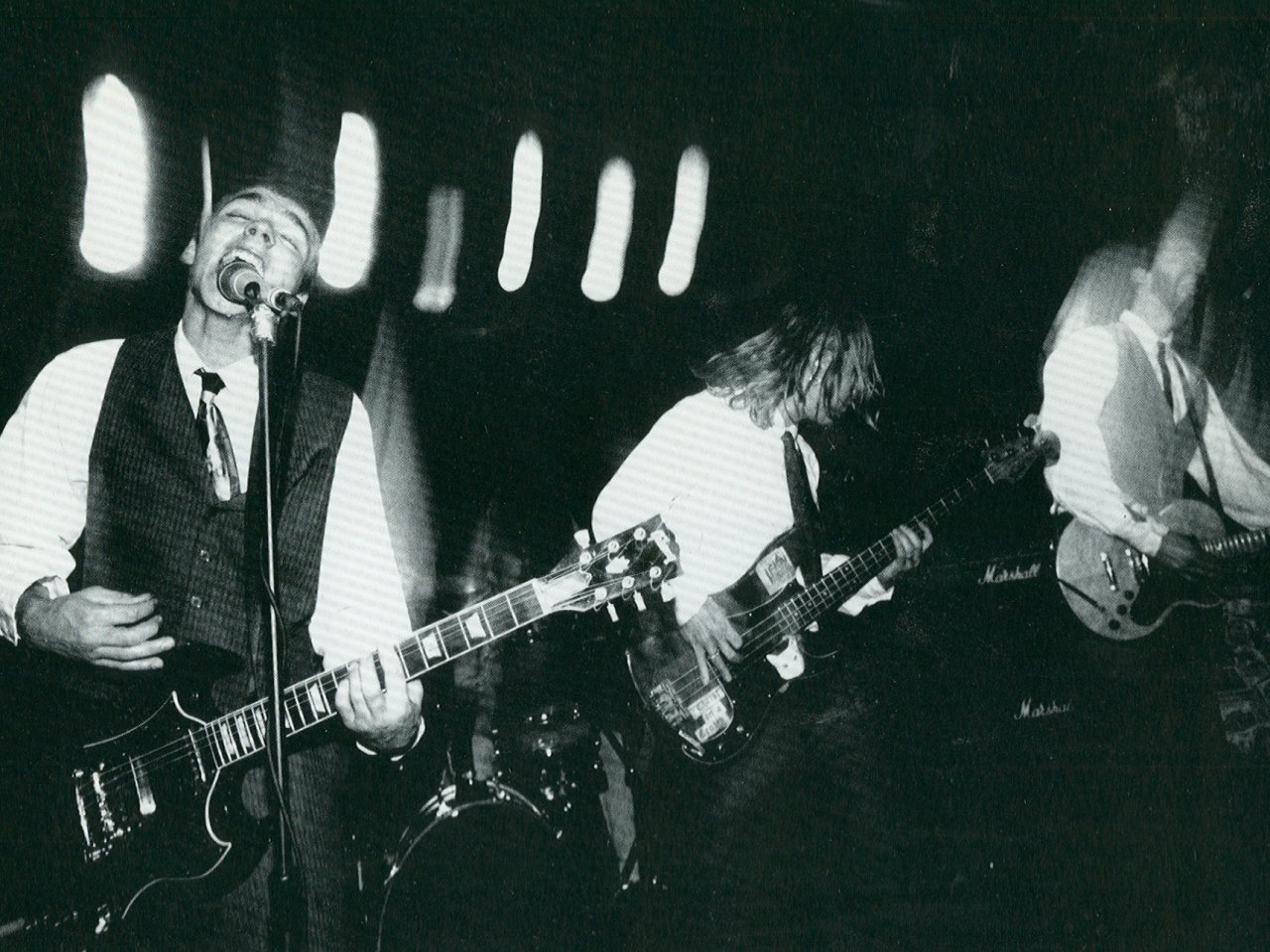

MacKaye’s beliefs about punk also had an effect on several other ardent Minor Threat fans, including 19-year-old Guy Picciotto, who founded a band in 1984 called Rites of Spring. While their music was no less raw or fast-paced, Rites of Spring were almost everything that hardcore bands – including Minor Threat – were not. Up to now, punk had mostly consisted of rough vocals shouted over the same three chords, repeated over and over again until they blurred into one tuneless mess. Rites of Spring, however, built their sound on melodic riffs, more complex songcrafting, and lyrics so emotional that fans who attended their concerts would often burst into tears as Picciotto half-sang, half-shrieked them into the mic. While Black Flag spoke of self-destruction or rising above the system’s control, Rites of Spring talked of love, forgiveness, and “falling through a hole in my heart.” The punk scene had never seen an act like this in its lifetime. Rites of Spring were innovators; pioneers of a new emotionally-oriented brand of rebellion through speaking out about their own innermost struggles.

As with anything new and unheard of, Rites of Spring’s distinctively emotional yet hardcore style drew many more aspiring musicians to emulate their sound. This led to such a surge in the number of bands embracing this style that the movement was later called the Revolution Summer of 1985. In the same year, Thrasher Magazine described the bands behind the Revolution Summer as – you guessed it – “emo-core” music. It’s worth mentioning that both Ian MacKaye thinks that “emo-core” is one of the “stupidest fucking terms” he’s heard “in his entire life,” and Guy Picciotto still doesn’t really understand to this day why he’s being called the “creator” of emo music. But neither does it matter. A new genre had been born. The first days of emo had well and truly begun.

The ’90s: The Rise of the Soft Boys

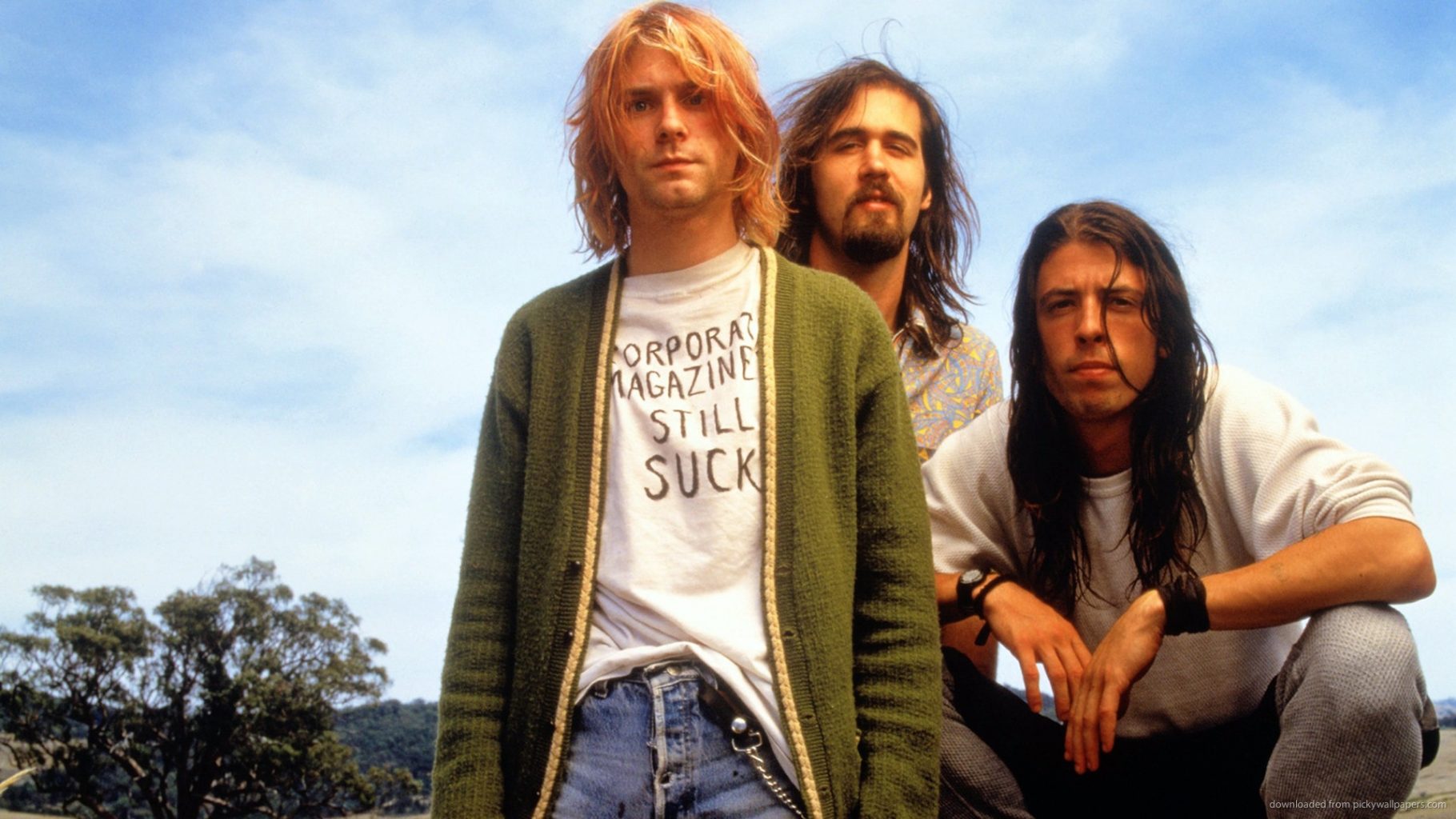

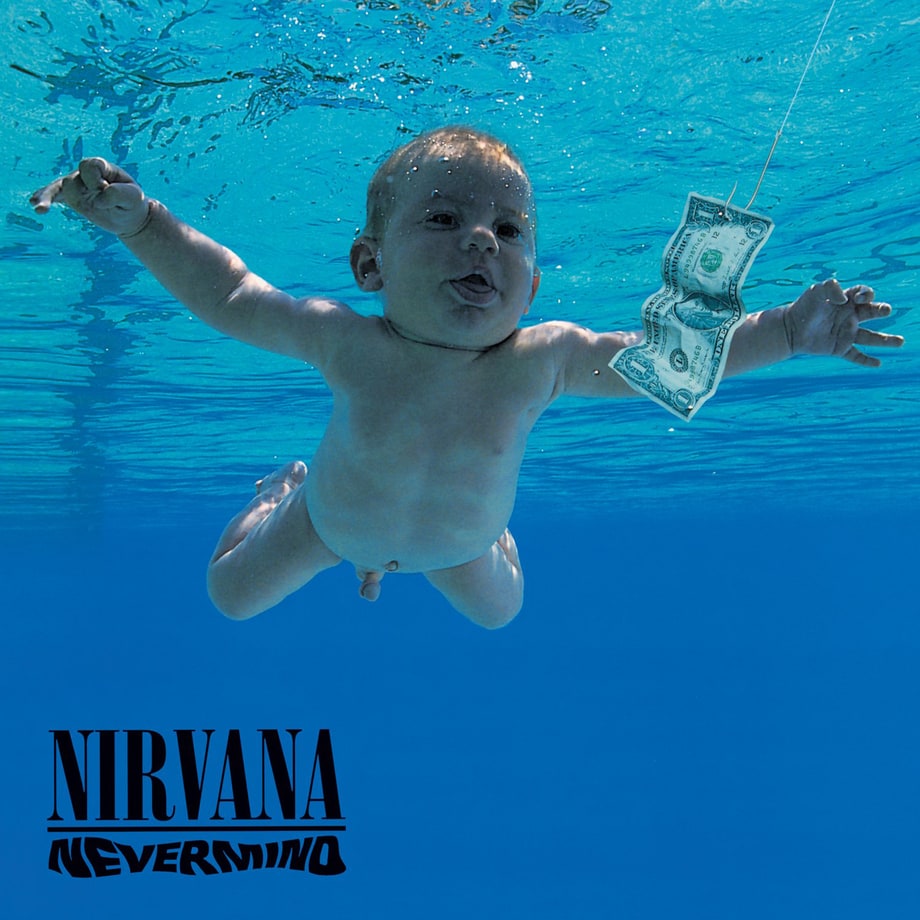

It all started with Kurt Cobain. No, I’m not about to claim that Nirvana was an emo band – those guys are definitely a grunge outfit through and through. Nirvana’s unprecedented mainstream success, however, did help propel emo into the spotlight. After Nevermind was released to both critical and popular acclaim in 1991, record labels began to mine the previously untapped pools of talent in genres of rock music that had previously remained underground – one of these genres being, of course, emo music. Suddenly, everyone wanted to be friends with the kids who previously had their faces shoved into locker doors. Love it or hate it, ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ was the anthem of the moment, and nothing could stop guitar music’s return to the top.

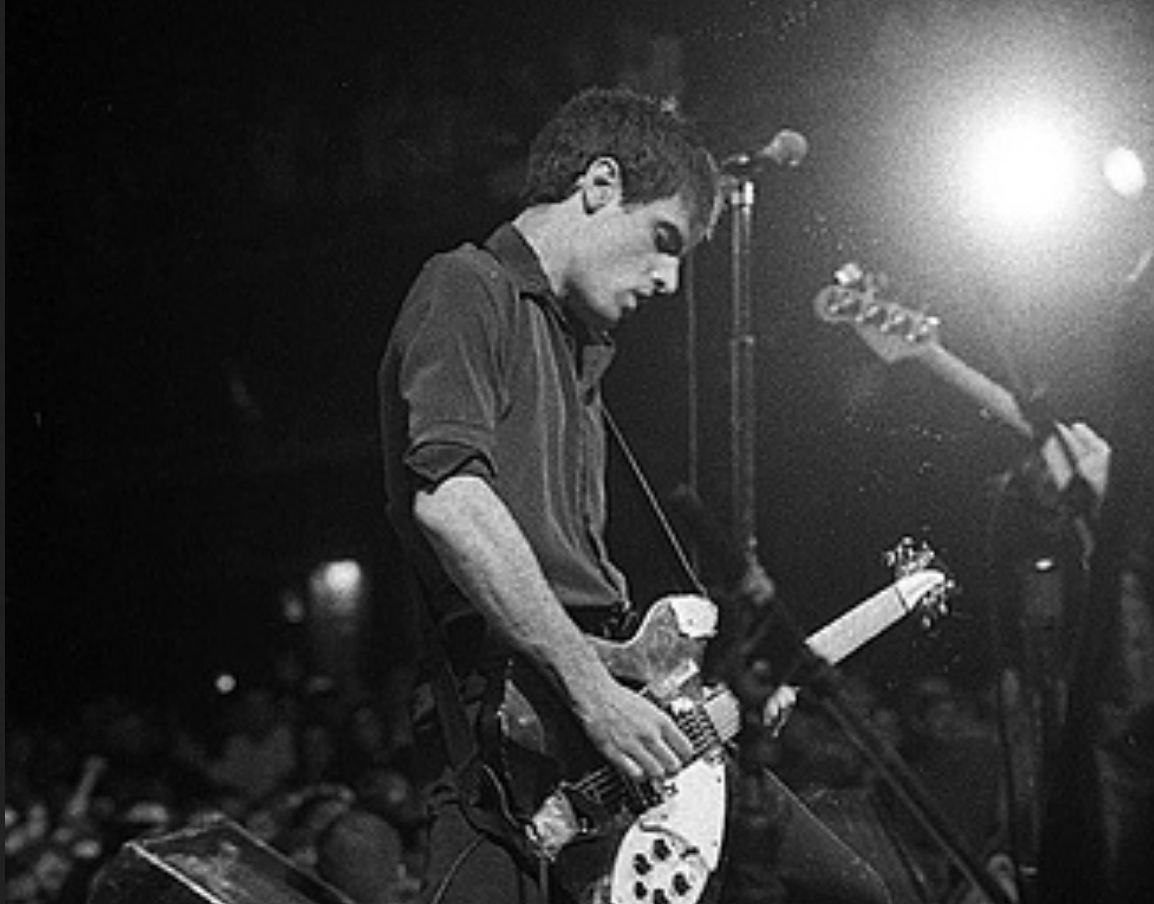

But as I said earlier, emo does not equal grunge. Those who rose to the forefront in the ‘90s did not sound very much like Nirvana at all, nor did they reach the same heights of fame. After Rites of Spring disbanded prematurely in 1986, two more seminal emo bands rose to fill the gap – New York’s Jawbreaker and Seattle’s Sunny Day Real Estate. Both bands also broke up in the mid to late ‘90s, but their musical legacy was one that would shape emo for years to come. Where Nirvana was once again perpetuating the idea that the future of guitar music lay in four-chord progressions and simple, methodical licks, Jawbreaker and Sunny Day Real Estate proved more ambitious; incorporating polyrhythms and dulcet progressions so far advanced from the one-two build-it-yourself sound of grunge that they made ‘Come as You Are’ look like it was written by a toddler. The two bands didn’t exactly sound all that alike – Jawbreaker’s output displayed strains of hardcore punk left over from Rites of Spring, while Sunny Day Real Estate crafted lilting, melodic guitar hooks and sang in the nasal half-crooned, half-whined tones that would soon become signature to the entirety of the ‘90s emo scene. These bands’ two most important albums set in place the cornerstones of the two strains of emo present today – Jawbreaker’s mostly fast and frenetic 1994 release 24 Hour Revenge Therapy pretty much founded pop punk, while Sunny Day Real Estate’s Diary is definitive of the mellower and more melodious side to emo.

Jawbreaker, and their frontman Blake Schwarzenbach in particular, was also pivotal in the assassination of the last remaining values of ‘80s punk. Schwarzenbach was another of emo’s larger-than-life founding fathers, whose personal life fans related to as closely as his own sensitive, candid lyrics. His endless charisma and doggedly loyal fanbase were the final nail in the coffin for ‘80s punk values – instead of a community-centric approach to music, the cult of personality and the importance of the individual struggle was truly back on trend. Bands taking on the ‘emo’ label all displayed the same empathy and passion in both their music and lyrics, and achieved relatively good success for it.

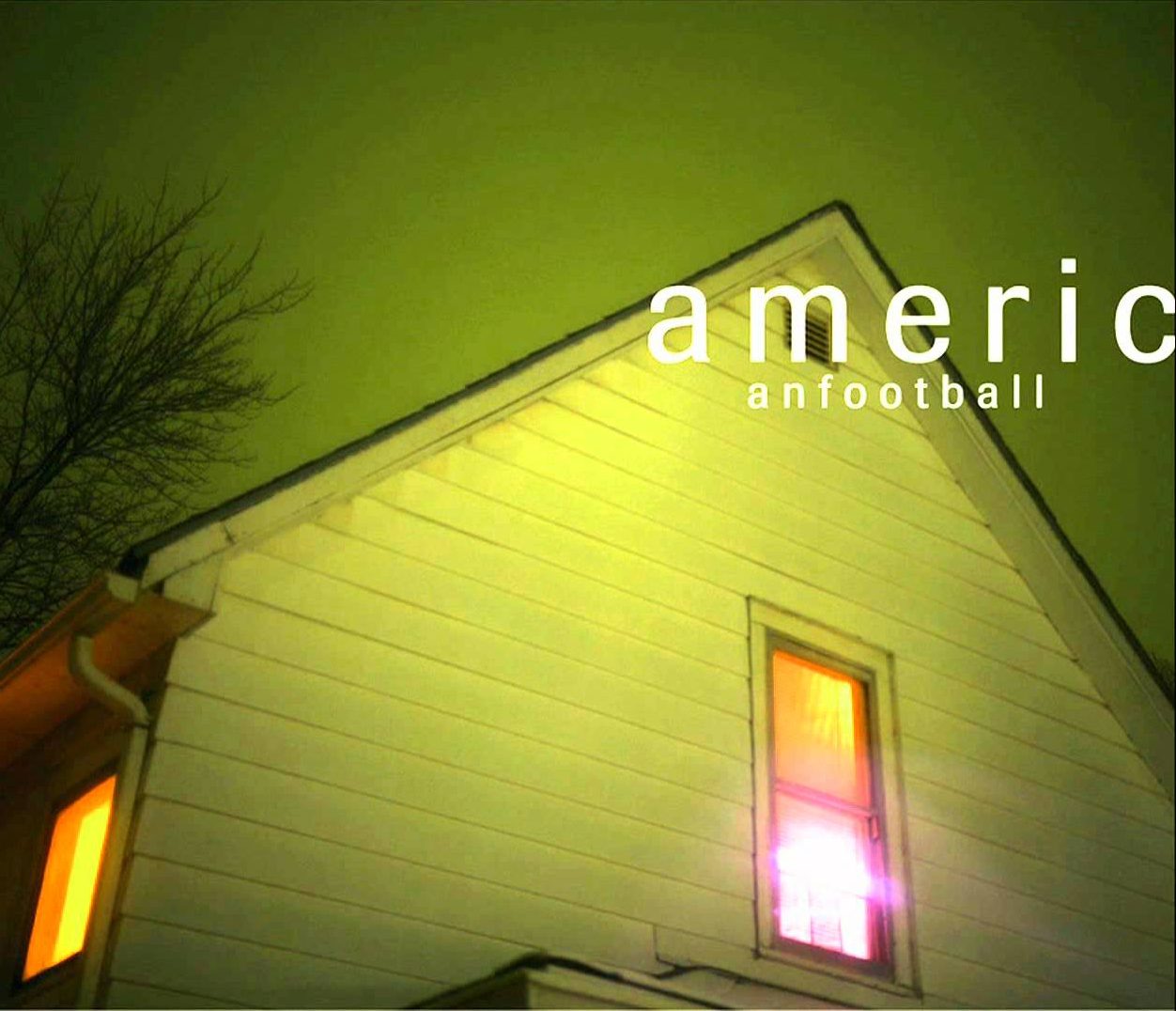

Arizona’s Jimmy Eat World, creators of ultimate throwback track ‘The Middle’, emerged in 1994 and signed with a major label just a year later (but did not peak until the next decade). Texas band Mineral, whose sound consisted of a reedy-voiced singer pouring his heart out about relatable everyday problems, received critical acclaim for their debut album The Power of Failure. And most notably, emo behemoths American Football released their self-titled debut in 1999, replete with sad saxophone solos and advanced guitar polyrhythms, and solidified themselves in the American consciousness as one of the most influential emo bands of all time.

All these bands were well-received, but never topped the charts like Nirvana did. Most of the emo bands that surged to the front of the mid-underground scene in the ‘90s disbanded before major labels could aggressively market them to the youth. Jawbreaker, Sunny Day Real Estate, and American Football remain, at most, bands with cult followings today, but if you were to stop a random person on the street and ask them if they’d heard of any of these bands, they’d probably say no. So, what changed? How did emo turn into the beautiful monster that we all know of today?

The ’00s: Welcome to the Emo Parade

On 11 September ‘01, a hijacked plane crashed into the World Trade Centre towers in New York and changed the world forever. America was shaken to its very core in the face of this tragedy. Understandably, the media were hysterical too; screaming about the need for a return to isolationism and austerity. Seeing as the media also serve as the supreme tastemakers of mainstream music, it was only logical that the “next big thing” in music would be a genre that was solemn, vouched for empathy and passion, and understood what it meant to feel real sorrow; be it lasting everyday troubles or grief on a worldwide scale. What genre fits that description best? You guessed it – emo.

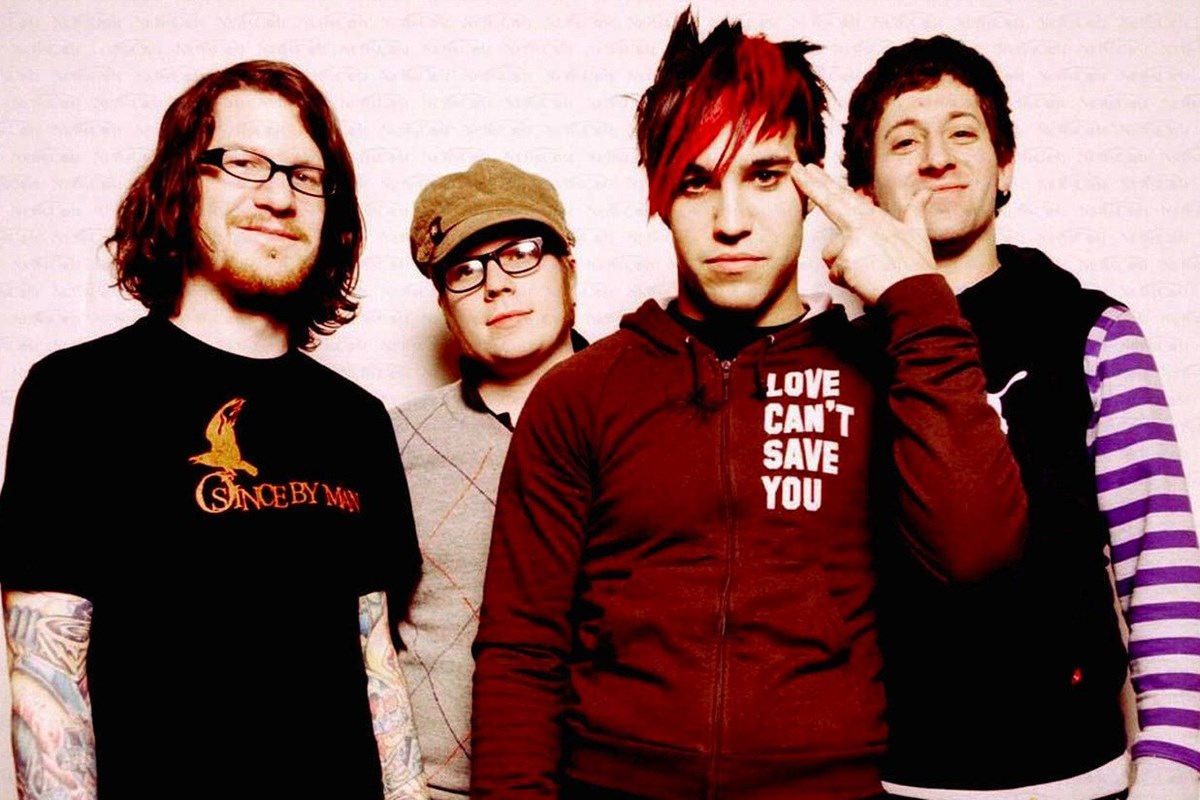

Remember those guys I mentioned earlier, Jimmy Eat World? After dithering around on their major label for almost seven years and achieving no real progress, their 2002 album Bleed American went platinum in the summer. Taking Back Sunday, another emo band you are most probably familiar with from your secondary school days, released Tell All Your Friends in the same year and were certified gold. And this was only the start of the emo renaissance. I probably don’t have to tell you a thing about the bands that come next. My Chemical Romance, Paramore, Fall Out Boy, and Panic! at the Disco – emo music’s awesome foursome – burst onto the scene like a freight train crashing into a brick wall, and the music world never looked back. All four bands received platinum certifications at minimum for the albums they released in this decade, and Panic! at the Disco’s smash hit ‘I Write Sins Not Tragedies’ was even certified quadruple platinum in 2016. Even the lesser-known artistes of the era received fantastic recognition – Long Island band Brand New, sometimes referred to as “the Radiohead of emo,” released The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me to critical acclaim and a lasting musical legacy akin to that of American Football. It was success all round for the boys and girls in black clothes.

It is worth noting, however, that noughties emo music began to deviate greatly from the two models of emo that Jawbreaker and Sunny Day Real Estate had laid down. In order to achieve success on the same stratospheric level that new-millennium rock bands like Simple Plan and The All-American Rejects were experiencing, emo had to assimilate sonically. Gone were the distorted, chaotic guitars of the ‘90s or the complex finger-plucked melodies. They were replaced by the same smooth, crisp, and rhythmic chord progressions with only the slightest hint of fuzz, evident on tracks as divergent as Simple Plan’s ‘Shut Up’ and My Chemical Romance’s ‘Helena’. The only feature that really set emo apart from the rest of the rock world at the turn of the century was its lyrics, which remained steadfastly loyal to the raw sentiment that their ‘90s predecessors had expressed. As emotive as ever, emo music was unafraid to tackle issues of grief, bullying, and mental health – themes rife throughout the discographies of My Chemical Romance, Fall Out Boy, and Paramore among others; from My Chemical Romance’s tear-jerking narrative of terminal illness on ‘Cancer’ to Paramore’s blistering revenge track ‘Misery Business’.

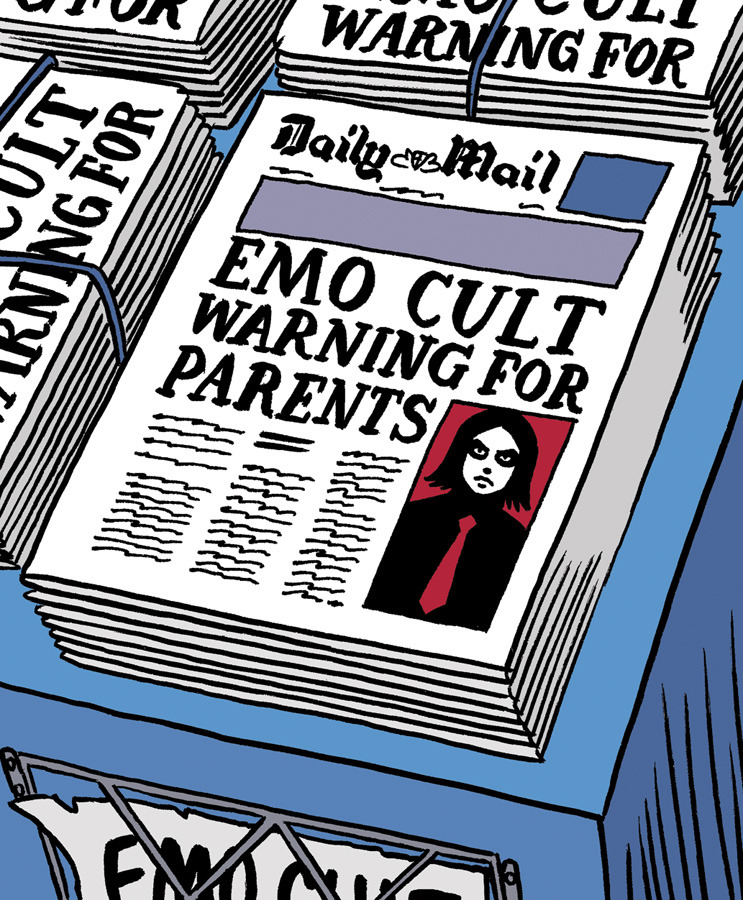

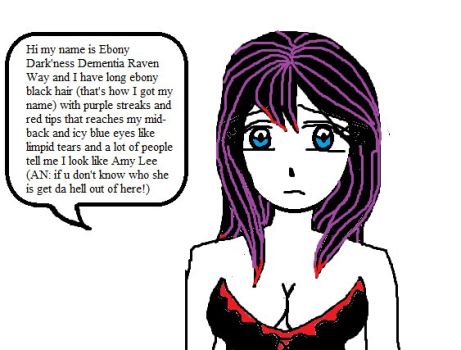

Through no fault of its own, this is how emo eventually became the butt of the joke. In a decade where depression was a buzzword and it was unbecoming to exhibit the slightest hint of frustration in the face of adversity, the public either saw emo as a deviant lifestyle that advocated self-harm and suicide, or an overly flamboyant movement that involved dressing like a goth and wearing excessive eyeliner. No thanks to countless disparagements and parodies from YouTubers and other rising stars of new media platforms – Ryan Higa’s viral video ‘How To Be Emo’ among them – as well as downright embarrassing antics from emo fans – see: the most infamous fanfiction of all time, My Immortal – ‘emo’ soon became a label that nobody wanted to associate with.

2010 – present: Emo is Dead… Long Live Emo

After almost ten glorious years in the limelight, emo has now sunken back into the underground depths from which it came. ‘90s emo remains firmly out of the public eye. The noughties emo awesome foursome is no more – My Chemical Romance has broken up, Paramore are now an indie rock band, and Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco are churning out synth-driven pop records. If emo was a person, they might just be in critical condition. Or… are they?

After emo almost flatlined in the earlier half of the decade, the genre is seeing another underground resurgence, thirty years after the original Revolution Summer of ’85. Their sound has evolved once more, too – now standing somewhere between indie rock, the Jawbreaker model of post-hardcore emo, and modern day garage punk. But unlike ‘85, it is fairly impossible to say where this new hope began. Los Angeles label SideOneDummy, renowned in the American/Canadian independent music scene, is partly responsible for injecting new life into the genre – their roster holds a healthy number of emo artistes, including cult favourites Title Fight and Andrew Jackson Jihad; the genre-bending one-man wonder Jeff Rosenstock; and Canadian punk powerhouses PUP and Pkew Pkew Pkew. Modern Baseball, one of the current decade’s emo frontrunners, also came to the attention of alt-rock heatseekers in 2014 with their sophomore album You’re Gonna Miss It All – a record that hearkened back to Jawbreaker’s 24 Hour Revenge Therapy while incorporating lyrics about modern life and anxiety in the Instagram age. In true ‘90s emo fashion, they promptly broke up three years later, on the verge of achieving further success. Other similar bands enjoying emo royalty status currently include The Hotelier, a band whose brand of slow-burning post-punk-inspired music has garnered them praise from even the picky folks at Pitchfork; indie rock oddballs The Front Bottoms; and Remo Drive, an up-and-coming trio from snowy Minnesota. And not forgetting, as every SoundCloud kid would attest to, hip hop has co-opted emo in the rise of emo rap.

While these bands remain, for the moment, as nothing more than indie buzz names, I wouldn’t be surprised if the second coming of emo isn’t too far off. Emo has, after all, displayed incredible resilience since its founding, and has shown that it can indeed change with the times. Gone are the cringe-worthy fans, the black Gothic clothing from Hot Topic, and the overall pretentiousness. The current diversity of sound within the genre itself and its overall increase in accessibility bode well for it too – an invitation for more alternative music fans to dive right in. So, will emo rise again? Only time will tell.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM