M’sian Short Film Tiptoes Over Beauty Standards In The Dance Scene & Promotes Body Positivity

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

When was the last time you consumed a piece of media that favourably depicted plus-sized men and women without exploiting their body for either comic relief or pandering?

If it takes you awhile to come up with an answer, then it proves that Malaysia, as well as the rest of the globe, has serious, deeply-entrenched issues with beauty standards and body representation in media.

Admittedly, picking apart all aspects of the media is an impossible task but at least today, we can start by dismantling those beliefs within the dance industry in Malaysia.

Introducing Lai Kah Chun, a 23-year-old aspiring filmmaker and graduate of IACT with a Bachelor’s degree in Media, Culture and Communication who has recently debuted a stunning short film/documentary on the struggles of being a plus-sized dancer in Malaysia.

Marrying his love for spoken poetry and photography, his work often revolves around “the complicated relationships between human beings” where he feels that his art is able to “allow the voices of the drowned to be heard, putting it front and centre thus highlighting them.”

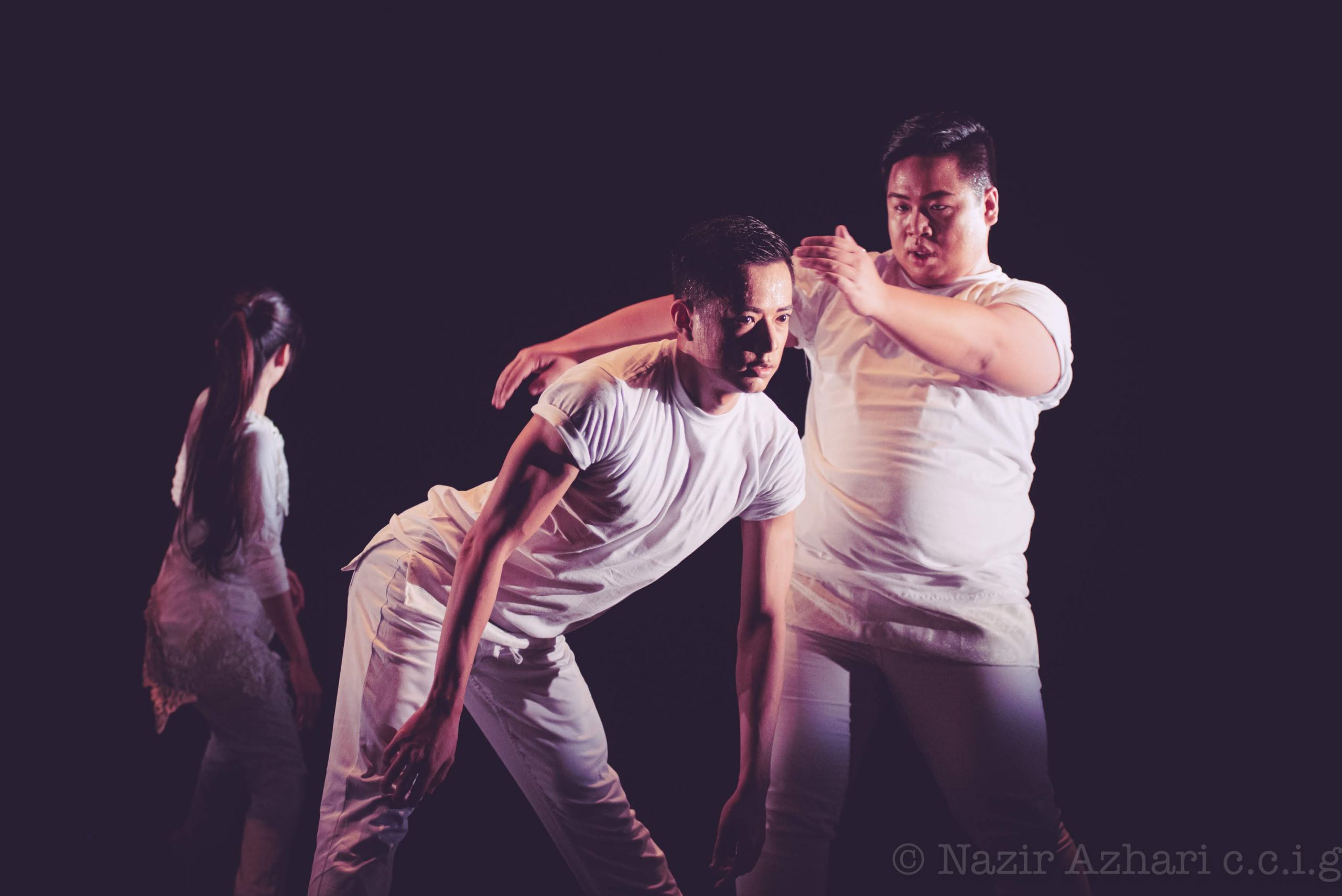

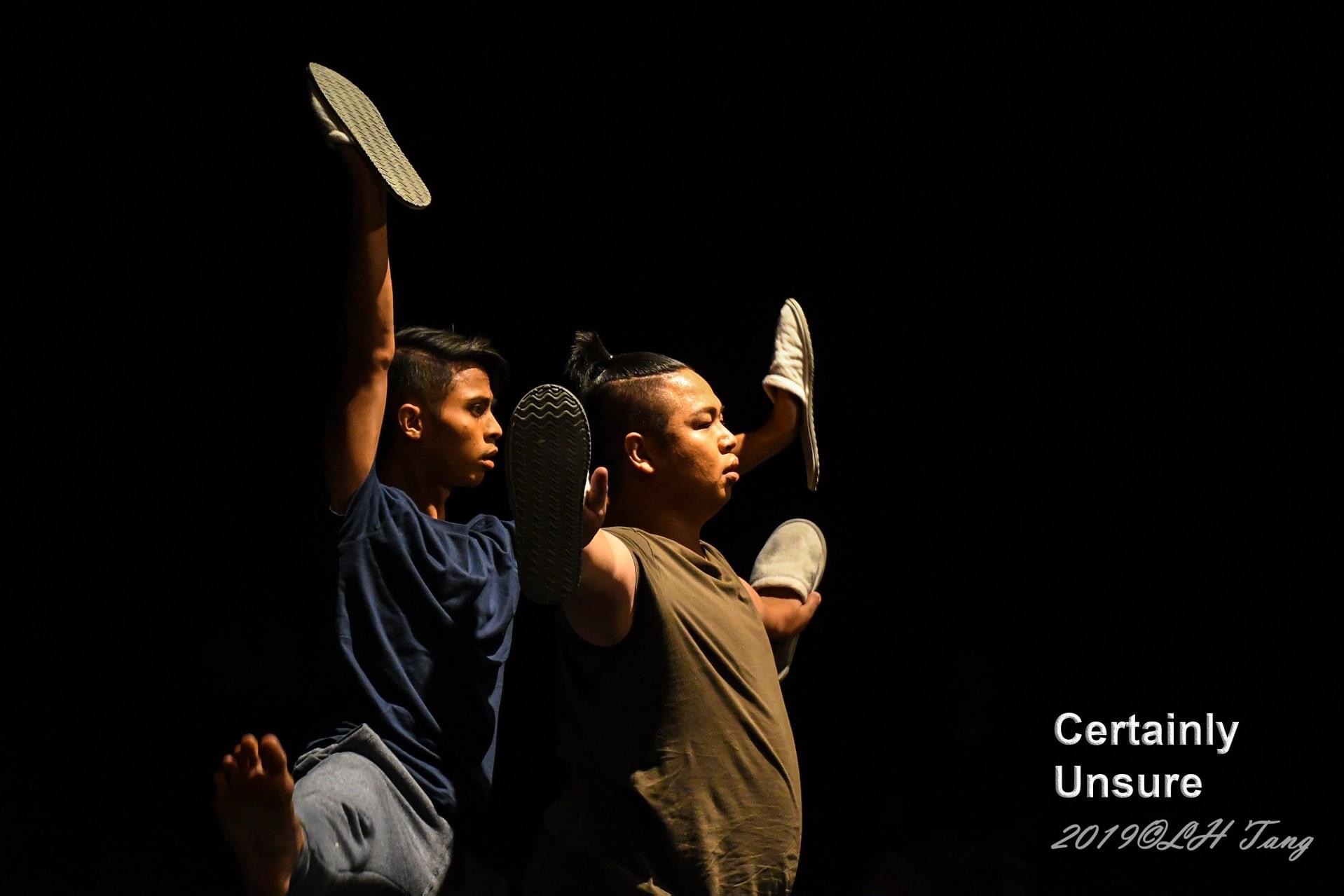

The star of his picture is Douglas Philip Labadin, a Sabahan 26-year-old freelance choreographer, dancer and student from Chulalongkorn University in Thailand. Fascinated by nature and animals, Douglas’s unique interests are often incorporated thematically into his work.

The film revolves around Douglas and his journey in overcoming the stigma, prejudice, ridicule and rejection that comes with being a plus-sized dancer in a field that is dominated by slender and lean bodies.

According to the dancer himself, “In a form that celebrates creativity and individuality, it baffled me how narrow minded these views can be.”

Watch the 7-minute short below:

His short sheds light on an almost untapped issue within the Malaysian lens which is why JUICE was interested in the Behind The Scenes of the documentary as well as hearing more from the director and the dancer involved.

With that, we managed to have a short yet insightful chat with the two on how the film came to be and the messages they wish to convey regarding these stereotypes.

Here is our conversation with Kah Chun (KC) and Douglas (D)….

How did you fall in love with dance and what made you continue despite the obstacles?

D: One of the first things that inspired me to take on dancing is a movie called High School Musical. I remember watching it for the first time, and I was amazed with the amount of talent that the movie had to offer. I aspired to be like those characters.

Although that was my initial drive, my first involvement in dance happened in secondary school, when a teacher saw me dancing away in an aerobics class. She invited me to come up on stage to join her, and before I knew it, I was part of the Cultural Club in school. The rest was history after that, as I fell in love with both dance and the local traditions of Malaysia.

The obstacles that I faced only appeared when I was in university, because it was where I decided to pursue dance seriously. Every time I was turned down for a part or excluded from a performance just because of how I looked, I just reminded myself that my time has not yet come and eventually, people will start seeing me for my talent.

It took a very long time for that to happen and even though these obstacles never disappeared from my life, I know now that there are a handful of people who believe in my talent.

When did you first realise that you were struggling to be recognized in dance due to your physical appearance?

D: Back in secondary school when I first started dancing, my physical appearance was never a problem. Teachers would normally praise me for taking up dancing, especially Malay dance, since I look Chinese. My body size was rarely the topic of discussion.

However, when I entered university, there were a few accounts of me being rejected just because I was plus-sized and looked different from the other dancers. In a form that celebrates creativity and individuality, it baffled me how narrow minded these views can be. That was when I realized that my physical appearance would hinder my growth in this community.

Why can’t dance be celebrated for its beauty and fragility, instead of how the dancer looks?

How do you think the media portrays dancers in an unrealistic way hence feeding into the limiting beauty standard that dancers must be slender and lean?

KC: I think it’s not a stretch to say that most if not all mainstream media lacks diversity in body image on screen. While there is some progress in promoting a range of bodies in recent years, this progress doesn’t necessarily penetrate the preconceived notion of what a runway model is, much less what a professional dancer should look like.

The media should highlight these taboo topics more because not only does it shed light on the issue at hand, it also helps pave the way for the younger generations to be more accepting and open minded towards the differences that each individual has. These unrealistic beauty standards prey on the mental health of viewers too but that is a whole other topic.

How have these standards proven detrimental/harmful to you and other dancers like you?

D: The perspective that dancers should be tall, lean and slim has been around for decades, and this perspective is mostly amplified by movies and TV shows that only showcase dancers who are of that quality. Even if there are dancers who are plus-sized, they often serve as comic relief and they are rarely taken seriously.

This makes it harder for audience members to come to performances with an open mind. They often come with the perspective that dancers should look a certain way, thus that’s all that they can see when a plus-sized dancer is on stage. No matter how hard the dancer tries to break boundaries and show to the audience that they can dance, it is really hard to convince them.

In other words, a plus-sized dancer needs to work twice as hard as other regular sized dancers.

Which part of Douglas’s story struck you as a pivotal moment thus inspiring you to craft and helm Tiptoe?

KC: I remember watching one of Douglas’s performances, and there was one choreography in particular that stuck out to me. The way I see it, that particular choreography did not highlight Douglas’s plus-sized body in a tasteful manner, instead it ridiculed his body in a humorous, almost disrespectful way.

I remember watching it until the end, not impressed at all at how the performance was executed, but people were cheering at the end and laughing at what they just saw. That was when I realized that I should do something to provide a different perspective into the life of a plus-sized dancer, and that was one of the stepping stones of how TipToe came to be.

Describe your style as a filmmaker by using the three most influential films to you.

KC: I find inspiration in stories that share the complication of lived experiences. These films don’t necessarily influence the way I write but they share similar values in what I’d like my writings to portray. In no particular order, Burning, Lady Bird and Moonlight are some of the films that inspire me.

These films burn slowly and beautifully. The rawness of emotions in the films coupled with the beautiful imagery places them on a whole new viewing experience.

Did any of the locations featured in the short hold any sentimental value to you or Douglas? If so, which ones and why?

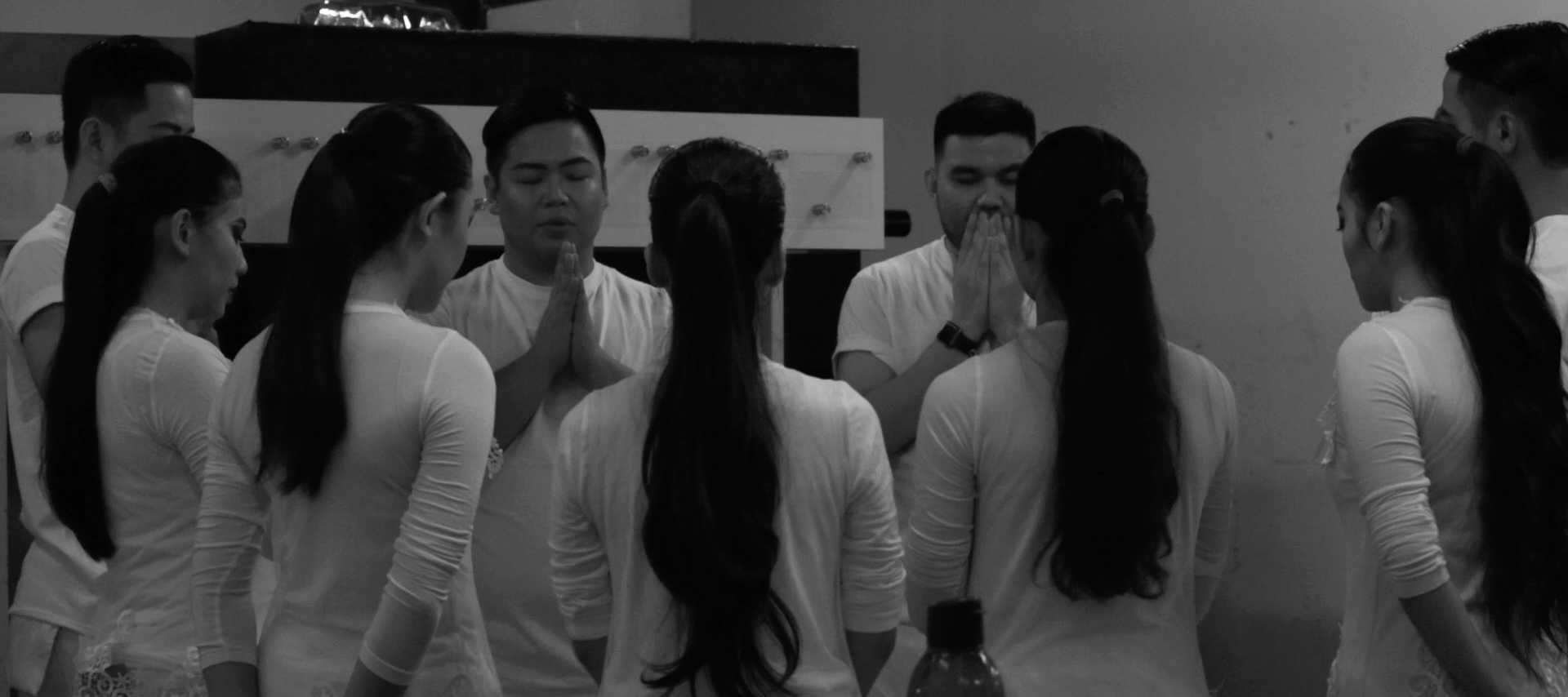

KC: This is rather personal but I think Douglas’s room holds some sentimental value. Throughout the production of TipToe, his room has become this safe place where we could share ideas. This resonated with the particulars of my own space, where no idea was too wild and no work is too ambitious. As long as I can put these ideas on paper, I am a step closer to putting these ideas on screen.

Ideas can spring from the oddest places, but it is in my room that I develop them. It is in my room that no stories are judged and his space reminds me of that strength in vulnerability.

D: One of the locations that holds sentimental value to me is the stage. Every time I go on stage to perform, it is the best feeling ever, be it a small scale production or a major league performance. Allowing myself to go on stage and be fully vulnerable is a scary thing to do at first, and it took me so many years to fully trust myself. However once I learned to let go, the feeling was tremendous.

It first came to me while I was performing for the Cultural Club back in secondary school, and that was when I realized I wanted to pursue dance as my career. Although the feeling comes and goes, it is that feeling that pushes me to go from one performance to another.

Coming out stronger after battling your obstacles head-on, what advice would you like to share with our audience when it comes to tackling beauty standards and changing an archaic mindset?

D: When approaching anything in life, there is no harm in keeping an open mind, and the same can be applied to the arts and performances in general. Once a viewer is able to indulge in something without having a preconceived notion on how it should be be or how people should look, then the viewer would be able to appreciate and focus on what the choreographer is trying to portray in the performance.

Additionally, do not put anyone into boxes in your head. Don’t assume that a plus-size person cannot be a dancer, don’t assume that a person of a shorter height cannot be a model and don’t assume that a person of darker skin cannot be a beauty pageant winner.

Don’t be prisoners of your own mind, instead indulge in the beautiful variety that the world has to offer, and celebrate how all of it can come together to create something extraordinary.

To support both Kah Chun and Douglas, follow their social media.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM