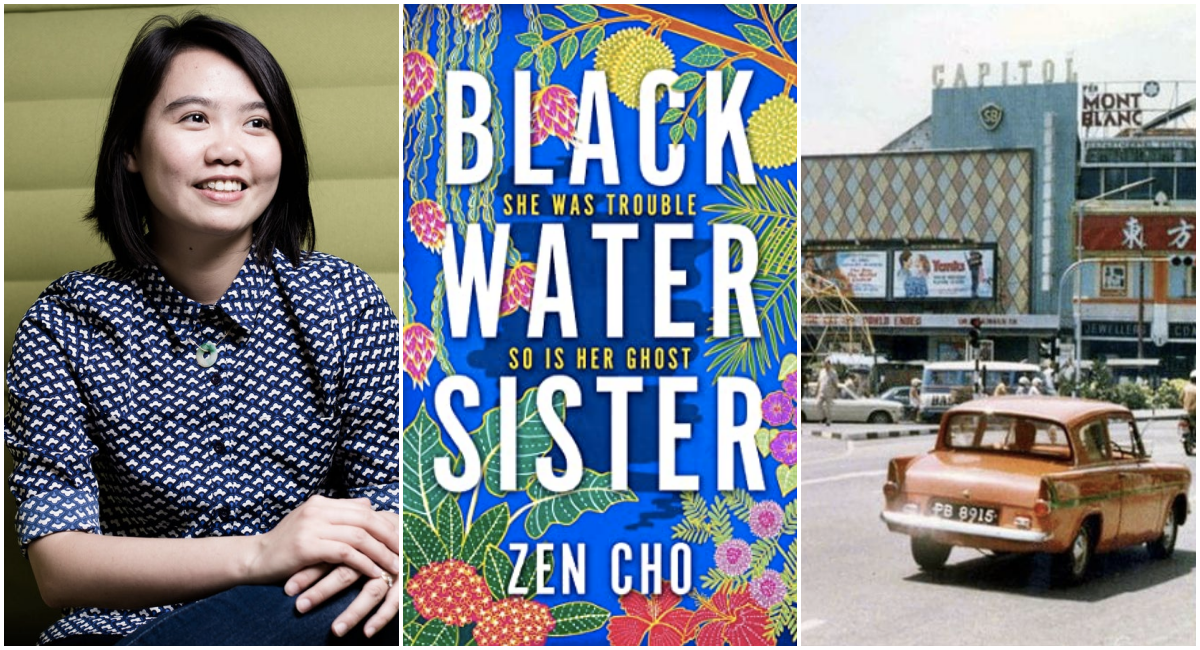

INTERVIEW: M’sian Author Zen Cho Talks ‘Black Water Sister’, Chinese Myths & Supporting Local Authors

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

“Does your mother know you’re a pengkid?”

Zen Cho’s latest novel, Black Water Sister opens with a piercing question targeted at Jessamyn Teoh, a 20-something who is not only struggling with the stress of moving back to Malaysia – a country as foreign to her as freedom of speech is to Malaysians – but also the nagging voice inside her head that claims to be her deceased grandmother and the fact that she is a closeted lesbian en route to a conservative country.

The internationally-acclaimed author tackles generational hardships towards women through the eyes of Jess, her mother and her Ah Ma by scaling through the culturally-rich streets of Penang and the history that is deeply-rooted within the temples, cafes and gentrified neighbourhoods.

Learning about the elements of superstitions, spirit mediums and deities, Jess acts as a vehicle for her grandmother to avenge her community against a capitalistic gang boss who threatens to tear down a temple in her family’s hometown.

While doing this, she reconnects with her familial ties and aims to regain control over her body and her autonomy as a queer woman in Malaysia.

JUICE received the grand opportunity of chatting with Zen about Black Water Sister, her experiences growing up in Malaysia, the plights of modern day Malaysian women and the importance of reading books centred around our culture. Without further ado, here is our interview with her…

Black Water Sister is rooted in reality but elevated by its complex and culturally-rich ties to fantasy and superstitions. What inspired you to write this genre into a Malaysian setting with an LGBT character as its protagonist?

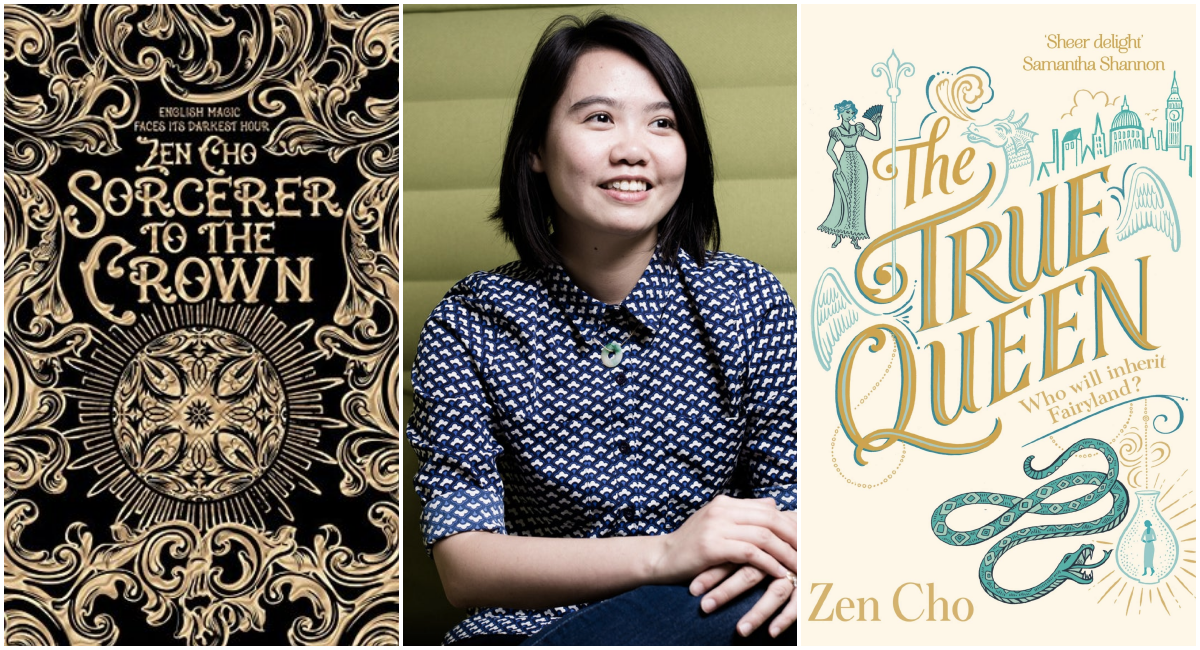

There were two specific inspirations for Black Water Sister. My first two novels, Sorcerer to the Crown and The True Queen, were historical fantasies set in early 19th-century Britain, written in a deliberately archaic voice.

While writing them, I spent a lot of time on the Oxford English Dictionary website, looking up old words that have largely fallen out of use, because I felt using those words would help give readers a sense of entering a magical alternate world.

One of the words I came across was ‘hagridden’, which basically means ‘stressed’, but also has a more literal meaning of being cursed or ridden by a hag or witch. It gave me the image of a young woman who’s being ridden around by her terrible ancestors and I thought, there’s a story there.

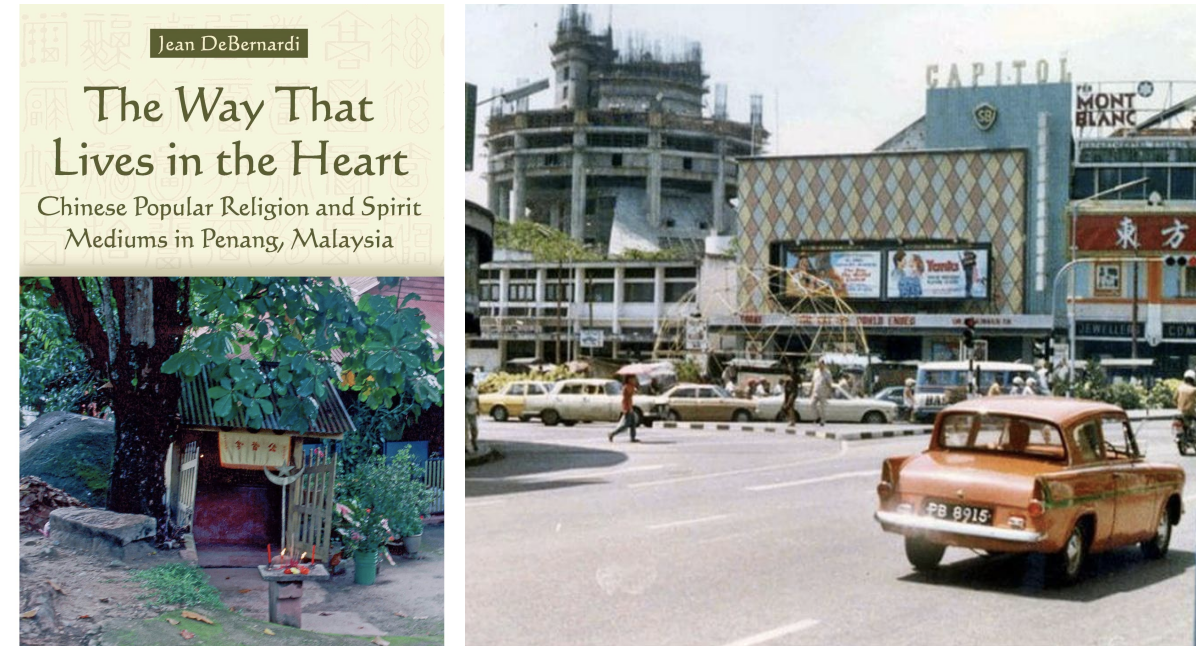

The second source of inspiration came when I read The Way That Lives in the Heart by Jean DeBernardi, which describes DeBernardi’s field research into the practice of Chinese folk religion, particularly spirit mediumship, in Penang in the 1980s.

My family followed the usual syncretic mix of Buddhism, Taoism and Chinese folk religion when I was growing up, but because they are very superstitious, they never really explained anything about the temples we visited or the gods we prayed to.

DeBernardi’s book gave me an intellectual framework for the beliefs I grew up around, and it was so rich in anecdote and story. It was the combination of that initial spark of an idea about a “hagridden” young woman and the desire to explore spirit mediumship in fiction that gave birth to Black Water Sister.

It’s hard for me to say why the protagonist Jess is gay.

That part just came to me. It would be as difficult for me to explain why some of my protagonists are straight, but oddly enough nobody’s ever asked me to do that.

Ah Ma is definitely a force to be reckoned with. Her snappy comebacks and fierce determination for justice is a true depiction of a feminist. Was she inspired by anyone that you know in real life?

Ah Ma is a lot more given to criminal behaviour than my real-life grandmothers, but I suppose she was inspired partly by them – particularly my paternal grandmother, who, like Ah Ma, worked as a rubber tapper to support her family.

They both had much more difficult lives than I have had, with fewer advantages, but they were strong, independent-minded women. I draw a lot of inspiration from them and all the other bossy, funny aunties I know.

The language barrier and slangs that are interchanged between Jess and Ah Ma can sometimes result in some pretty comedic back-and-forths. This is evident in almost every multi-lingual Asian household. Being bilingual yourself, what are some of the funniest blunders you have made while speaking in your native tongue?

I consider Malaysian English my native tongue, and my English is excellent, so I can’t really think of any amusing blunders I’ve made speaking that.

I guess if you say Hokkien is one of my native tongues, because my parents speak it – though I don’t, plus we are technically Hakka – I once misheard ‘chu kee tia‘, meaning “my teeth hurt”, as “go outside and listen”. Which sounds quite similar, but maybe only to bananas like me!

Reading Black Water Sister feels like sitting in on a conversation with my own matriarchal figures, most notably my grandmother. The stories of hardship and pain that have been passed down alerts me of my privilege as a university-educated woman. Were there any stories that struck you personally and eventually led to the conceptualisation of the novel and its characters?

Like I said, I drew some inspiration from the lives of my grandmothers. Neither of them went to school so they were illiterate, and that’s something I think about a lot, because reading and writing have been so important to my life and so foundational to my identity.

I would be a completely different person if I hadn’t had the opportunity to be educated. So that ended up being one of the main themes of Black Water Sister – the idea that who you are depends on when and where you are.

Writing a novel with an LGBT female character is widely accepted in other countries but not so much in conservative Malaysia. However, your decision to write Jess as a queer character is very much welcomed by us because it results in representation for young queer girls in the country. What do you have to say to your Malaysian female queer readers who see themselves in Jess?

I think everything I have got to say to queer Malaysian women is in Black Water Sister. If I had to boil down the message to a line or two, it would be something like: you matter, and you should get to be a whole person in all the worlds you live in.

It sucks that that isn’t how it works for many people.

There are many elements of the Chinese culture that enrich the novel. From the language spoken by the characters to their various superstitions and ties to religion, it’s clear that Black Water Sister is very personal and relatable. This proves that own-voices novels are much needed especially for Malaysians. Do you believe that there is a shortage of Chinese representation in Malaysian books?

It depends on your definition of ‘Malaysian books’. Ethnic Chinese writers tend to be overrepresented among internationally published Malaysian Anglophone writers, if anything. I assume that’s not the case with books published in Malay.

Specifically Malaysian Chinese representation is certainly rare – in my genre of fantasy, for example, the writers of Chinese Malaysian heritage that I’m aware of may draw on Asian or Chinese culture, history and mythology, but not Malaysian Chinese culture as such.

So that’s something I always enjoy seeing.

Being an only child in an Asian household carries a lot of responsibility. Jess struggles with this when she is struck by the dilemma of having to choose between making her parents proud or chasing after what she wants in life. Why do you feel that there is more pressure within our culture and society for youths to achieve greatness?

I think there’s a very strong sense in Asian and immigrant communities of parental sacrifice.

Immigrant parents in particular will often have suffered a lot to raise their children in foreign countries that aren’t always welcoming, so that can bring with it a corresponding burden on the children to justify that suffering and sacrifice by their success or compliance.

There’s obviously also the influence of culture and tradition, the weight of societal beliefs about what you owe your family.

That tension between family responsibility and personal freedom is something that’s been well covered in lots of fiction, but what I wanted to bring to it in Black Water Sister was a sense of the humanity of Jess’s parents and the tenderness of her relationship with them, even with all the damage that pressure causes Jess.

Religion varies across all races but one thing remains the same, the belief in the supernatural. For Malay-Muslims, we have several taboos or pantang larang (to keep it local) that are passed down for generations – even to self-proclaimed modern zillennials. What are some of the taboos or superstitions that are the most prominent in your family?

We were brought up not to step on books, shout at the wind, or talk about unlucky things like death. Apart from that, the taboos and practices were pretty standard for Malaysian Chinese – no sweeping the house or quarrelling during Chinese New Year, avoid risky activities in Hungry Ghost Month, and so on.

Black Water Sister is a tale that interconnects the stories of women of different generations and personal struggles. However, despite the years that have passed, Malaysia is arguably stagnant when it comes to women’s rights and issues as illustrated by the annual Women’s March. Do you still keep up with Malaysia’s societal issues? If you do, what are some that concern you the most when it comes to women?

With a small child and two careers it’s questionable whether I keep up with societal issues anywhere, but I suppose you can say I do keep up with what’s going on in Malaysia, thanks to social media.

What worries me is how relatively backward the public discourse is in Malaysia on women and women’s rights – the level of what’s considered acceptable misogyny is much higher than, say, in the UK, where I live now. The wide acceptance of religion as a justification for the repression and exploitation of women and girls is also really depressing to me.

The way in which you paint the picture of Penang through your words is very accurate and lush. I can tell that you have a deep fondness for the state. When you were in Penang, where were the places that you would frequent and what are some of your fondest memories?

I have relatives in Penang so visited annually throughout my childhood, and also lived there for a couple of years. As an adult my relationship is much more that of a tourist, but it’s a fun place to be a tourist.

I like the old buildings and busy streets of George Town, but probably what I like most about Penang is that it’s not just ornamental, it feels very lived in. I like the arts scene, the markets and the hipster cafes – some readers have recognised the café China House in my book, for example.

You’ve previously worked with local publisher, FIXI on a book about sci-fi and magic set in Malaysia. What was your process when it came to collecting stories for the anthology and did it spur you into dedicating a whole novel surrounding this premise?

Yes, I published a short story collection with Fixi called Spirits Abroad. That went out of print but has now been picked up by a US press, Small Beer Press, who rereleased it this year in a beautiful expanded edition.

The process for collecting the stories was quite straightforward – I just put together all the stories I’d written that seemed decent enough to be published, and hoped the publisher would agree. Then I cut some of the stories out because Fixi said they didn’t want the book to be too long.

The stories did have similar themes to those handled in Black Water Sister, but doing the collection itself wasn’t a spur for writing Black Water Sister. It’s more that the novel is a manifestation of my continuing interest in these themes. I probably would have written the novel five years ago if I could, but at that time I didn’t have a suitable novel-length idea, or the writing skills to realise it.

Lastly, who are some of your favourite Malaysian authors whom you believe need more recognition when it comes to local readers?

I’ll focus on writers who are published locally and regionally, since I think the internationally published writers are more visible.

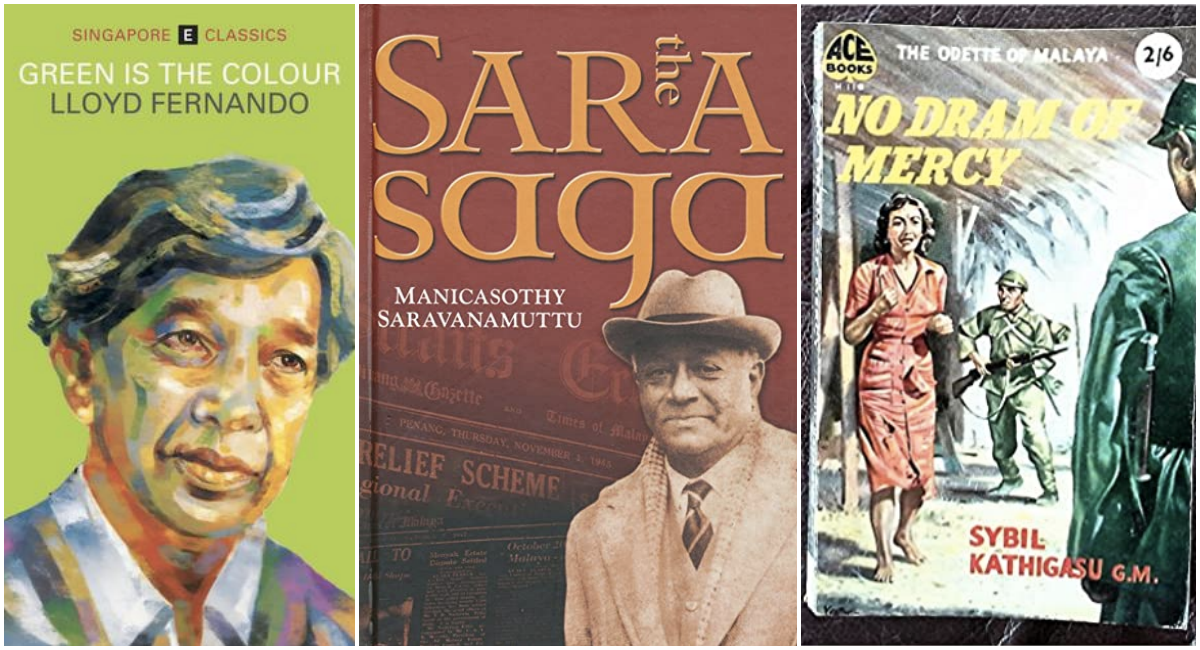

I recently read Lloyd Fernando’s post-May 1969 novel Green is the Colour (Epigram Books) and found it moving and thought-provoking – all the dialogue is in Manglish and having that be so unmarked was a great pleasure.

Thinking of another Sri Lankan who adopted Malaysia as his home for a time, I found Manicasothy Saravanamuttu’s memoir The Sara Saga (Areca Books) extraordinarily entertaining. He was a keen cricketer, an Oxonian and newspaper editor who lived in Penang during the Japanese occupation.

Staying on the memoir theme, Sybil Kathigasu’s No Dram of Mercy (Prometheus Enterprise) is a slim volume recounting her activities during World War II treating anti-Japanese guerrillas and her detention by the Japanese as a result – worth reading for many reasons, but the forcefulness of her personality is what has stuck with me. You really get a sense of who she was from her writing.

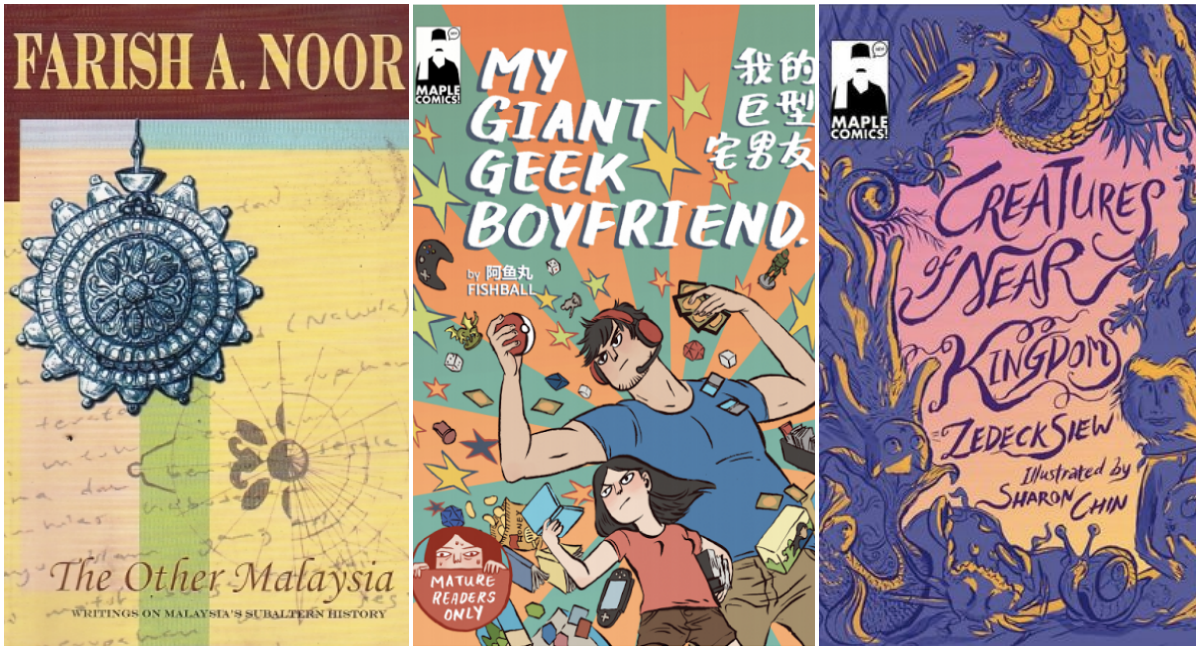

On history, Farish Noor’s essays have taught me a lot about Malaysia – he’s an academic, but writes in a very accessible style. The Other Malaysia (Silverfish Books) or What Your Teacher Didn’t Tell You (Matahari Books) are good places to start.

And finally, we have some great comics artists. I like Maple Comics’ books, e.g. Mimi Mashud’s travelogues and Fishball’s My Giant Geek Boyfriend (on Webtoon as My Giant Nerd Boyfriend). Creatures of Near Kingdoms by Zedeck Siew and Sharon Chin isn’t quite a comic even though it is published by Maple; it’s an illustrated bestiary of imaginary plants and animals native to Southeast Asia.

It’s prose, but feels like reading poetry.

To keep up with Zen Cho, follow her on Twitter.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM