Yes, Period Stigma Still Exists In Southern Asia And It’s As Harmful & Prevalent As Ever

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

In an ideal world, menstruation would be celebrated as a beautiful and symbolic manifestation of fertility and nature, empowering people who experience periods with a sense of connection to their bodies and cycles.

However, the harsh reality is that in South and Southeast Asia, period stigma continues to cast a dark shadow, leaving lasting scars on countless lives.

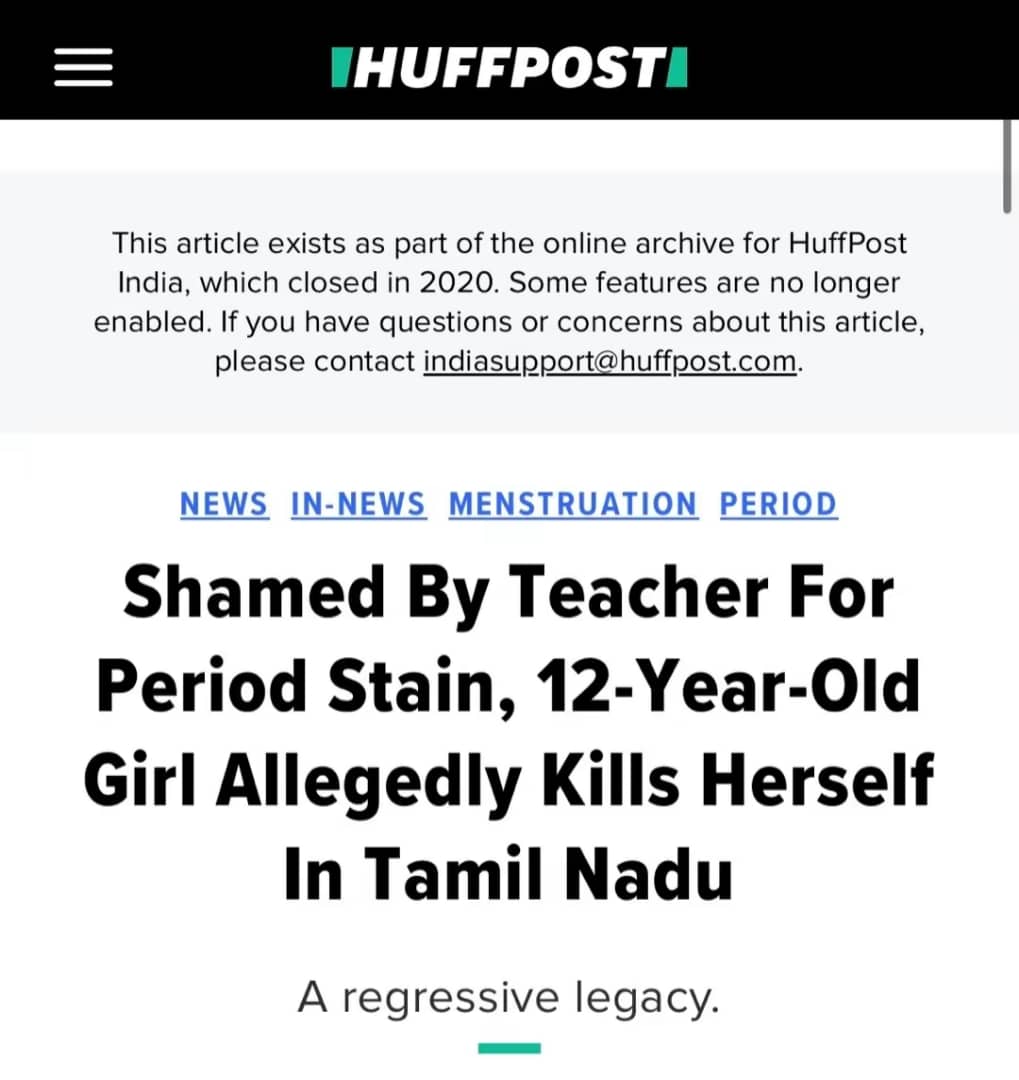

Tragically, the shame associated with menstruation has reached alarming levels, driving some to the brink of despair and even self-harm. In several heart-wrenching instances, the burden of shame has resulted in cases of suicide and murder, highlighting the urgent need to confront this issue head-on.

This article recounts real-life cases of suicide, self harm and violence. Reader discretion is advised.

These cases are among the many that have occurred within the past decade. Note that these are the ones that have been reported in mass media; a substantial amount of these ‘blood for blood’ cases and situations where menstruating women are disrespected go unheard:

The spectrum of ‘period experiences’ is wide in the areas of South and Southeast Asia. For some, it is linked to positive or even wholesome memories, usually ranging from exchanging a quick smile with the girl who hands you a tampon in a time of need, to those ‘canon experiences’ where you get a friend to walk behind you for a subtle ‘spot check’.

For others, it’s grimace-worthy recollections of the times your heavy flow led to stained clothing or bedsheets. It’s the boys pointing at you, laughing as you try to figure out what the joke is. For me, it’s my grandmother reprimanding my cousins and I, holding up her bloodied fancy chair pad on Chinese New Year, asking which one of us had left “this disgusting stain” on it. It’s my older cousin quietly admitting to it, choking down guilt as if she’d done it on purpose.

For many of us, the period stigma is something that is engrained into our beliefs from the minute we hit puberty.

We know our menstrual cycle is not something we cannot discuss openly, especially in front of men. We know that we have to hide our sanitary pads in our pockets when we head to the toilet at school, and we know to be careful not to let any blood seep into our clothing not just because it’s difficult to wash out, but mainly because the experience of having people spot your period stains is one that is hard to live down.

In some way, shape or form, we’ve been conditioned to link our menstrual cycles to moments of potential shame, and while it does not always result in physical harm or death, it lends our society an invitation to humiliate people using one of the body’s most natural, and supposedly sacred cycles as a crutch.

One of the most distressing aspects of this stigma is witnessed in India, where women, over several generations, have faced humiliation and ridicule if their menstrual stains become visible – even from their own families. As mentioned above, this has too often led to death that comes from the belief that one’s honour has been tarnished if they fail to conceal the signs of menstruation.

In Malaysia, the period stigma does not commonly result in self harm or other forms of violence, but its consistent reputation as a taboo topic and the way menstruation still serves as a basis for insults and jokes highlights our unfulfilled role in supporting surrounding nations in their efforts to cease their struggle – as well as our own.

These ‘jokes’ and the normalisation of them are among the reasons why people, including children, are hesitant to reach out and ask for basic human necessities

Period poverty, which refers to the lack of access to menstrual products and adequate menstrual hygiene facilities is mainly linked to low income and lack of access to menstrual products. However, other factors that amplify this struggle are the societal stigmas and cultural taboos surrounding menstruation can lead to further isolation and reluctance to seek help or information about managing periods effectively.

FYI – period poverty in Malaysia has now been reported to be at a level that is “not concerning”, but this does not mean that we have completely overcome it.

It’s also important to note that the human experience in general varies from region to region and changes with age.

An instance of period shaming may be laughable for an adult in a progressive society, but is enough to drive a vulnerable child to suicide.

Despite multiple movements, media efforts and even films made to raise awareness regarding the topic, this harmful practice continues to perpetuate the notion that menstruation is something to be concealed and regarded as unclean, adding to the emotional anguish women experience during their monthly cycles.

The roots of this stigma are not always, but often entwined with cultural and religious beliefs.

In many Asian communities, menstruation is perceived as a state of being ‘unclean,’ leading to a tradition of segregating menstruating women during their periods. But how much of this is religiously accurate – more importantly, how much has been taken out of context?

This practice, combined with widespread ignorance about the natural process, fosters a prevailing perception that menstruation is disgusting and dirty.

In this piece, JUICE speaks to four women – hailing from different areas of Southern Asia to discuss their personal encounters with the period stigma that plagues their home countries:

Gillian

As a 20-year-old college student from Singapore, Gillian had an unfortunate experience that highlighted the persistence of the period stigma. In her rush to change her sanitary pad during a break, she forgot to dispose of her old pad properly and left it wrapped on top of the toilet tank. It was a mistake on her part, but she could not have anticipated the consequences.

To her shock, someone took advantage of the situation and posted an anonymous message in the college group chat on Facebook, publicly shaming her for the “absolutely gross” mistake. Not only did they detail her personal hygiene oversight, but they also named her and her course, making the embarrassment even more intense.

What hurt Gillian the most was the realisation that the person behind the message was likely a fellow woman and someone who knew her personally. The fact that they would use such a private and personal moment to humiliate her rather that reprimand her to her face was deeply hurtful.

Despite not knowing who was responsible, Gillian’s experience served as a painful reminder that period stigma still existed, even among her peers in an educational setting. The incident also made her acutely aware that the taboo around menstruation would not easily fade away.

Afifa

Afifa’s experience in Bangladesh was one of embarrassment and shame when she unknowingly bled through her uniform at school one day. Her period arrived unexpectedly early, catching her off guard. As she stood up to collect her test papers from the teacher’s desk, a group of people noticed the stains on her skirt. They sniggered and made hushed comments, leaving Afifa puzzled and confused.

Unaware of what was happening, Afifa went on to place the test paper along with the books under her desk, unknowingly touching her copy of the Quran. In a sudden outburst, her classmates shouted at her and forcibly took the Quran from her hands. It was then that they informed her about the period stains on her skirt. The incident left her feeling not only embarrassed about her period but also as if she had disrespected her religion.

“We have turned matters of faith into excuses for mistreating each other, and to me, that goes against the whole concept of religion,” she says.

In her distress, Afifa realised that her peers’ behaviour was rooted in the lack of awareness and understanding about menstruation, particularly in relation to religious practices. While it is true that women are advised not to touch the Quran during their menses, Afifa had not known she was menstruating at the time and she knew that the situation could have been prevented if someone had kindly informed her about the stain without causing a spectacle.

Vinda

As a teenager growing up in the Philippines, Vinda’s experience with the stigma surrounding menstruation was not necessarily religious in nature but rather rooted in the perception that periods were disgusting and strange.

One of her most vivid memories was related to buying sanitary pads from the local store. One night, Vinda’s elder sister went to purchase pads for herself, but their neighbour discouraged her, explaining that a male cashier was on the current shift. recognising him as a friend from school, Vinda’s sister proceeded with the purchase. To her dismay, the cashier spread the news to half the school the next day, leading to her being ridiculed with the moniker “24cm with wings.” When the girls informed their parents about the incident, they were advised to ignore the taunts, as they were told it was “normal.”

Another distressing episode occurred years later when Vinda asked her father, who was on his way home from work, to buy her a pack of sanitary pads. Unfortunately, he came back empty-handed, explaining that it would be “weird” and “embarrassing” for him, “as a man,” to purchase such items.

Apart from cultivating values of respect in our society, efforts to dissolve the period stigma also require dispelling common public misconceptions and evidently, delving into the true essence of certain religions.

As mentioned before, in some traditional communities, menstruation has been viewed as ritually “impure”, leading to temporary restrictions or taboos during a woman’s menstrual cycle. These restrictions might involve limitations on temple visits, participation in certain rituals, or involvement in specific activities.

However, in reality, these religions usually hold menstruating individuals in high regard, recognising the menstrual cycle as a sacred and vital aspect of life. It represents a connection to the natural cycles of creation and regeneration, a cycle that is deeply revered and honoured.

Shanti, a veterinary student from Thrissur, India, explains this concept of ‘exclusion’ in Hinduism:

“Apart from the temple, menstruating women are also often barred from entering the kitchen while she’s on her menses. In some cases, a tinier hut-like space is built outside the home where the women will temporarily reside during her period.

Somehow, the narrative has been twisted to make it seem like the woman in question does so because she is ‘dirty’ and thus does not deserve to be in the same room as her other family members during this time. It’s shocking how widespread this idea has become, when a swift fact check would show that in our culture, menstruation is seen as a time of physical and emotional strain for women, and it is believed that they need rest and should not be burdened with household chores or other responsibilities during their period.

The idea behind such practices is to provide women with a period of rest and relaxation during what may be a physically taxing time for them. It is considered a time for women to take care of themselves and focus on their well-being without feeling obligated to perform daily duties. The family is also meant to care for her during this time, but often, due to the idea that she is ‘dirty’ they instead tend to avoid and neglect her.

“It’s not meant to be a form of exclusion, but an expression of utmost respect and appreciation for the woman.”

To dismantle the deeply entrenched period stigma in Asia, she also believes that it is crucial to promote comprehensive education about menstruation and its significance. Breaking down the barriers of silence and shame can pave the way for a future where menstruation is celebrated as a source of strength, pride, and unity.

Meanwhile, Afifa’s perspective on putting a halt to period stigma is thoughtful and highlights the importance of education and understanding at home – teaching children not to ridicule others based on their natural bodily processes is crucial for fostering empathy and respect.

She states that respecting the natural cycles of others’ bodies, regardless of whether one experiences them or not, is an essential aspect of building a compassionate and inclusive society.

“Understanding and supporting each other during menstruation can help combat the negative stereotypes and beliefs surrounding periods,” she adds.

Vinda spoke to us with an approach that came from a place of compromise.

“We do not need to embrace [menstruation] like the Western cultures do, where some even use the blood as paint for their artwork on canvas, but a basic understanding is all that is needed.

“Menstruation is already a painful process which unfortunately does not serve as a ‘Get out of jail free’ card for us to escape our daily responsibilities. We do not need the extra stress and hurt.

“We are born from blood and it’s time we realise that is a beautiful and complex concept that goes beyond jokes and insults,” she says.

Overall, their perspectives highlight the need for open conversations, empathy, and education to break the stigma surrounding menstruation in working towards a more understanding and supportive society for menstruating persons to feel safe in – and we couldn’t agree more.

If you are struggling with thoughts of suicide, self harm, or violence, or know someone who is, do not hesitate to seek help:

Talian Kasih

15999

Befrienders

03-76272929

Agape Counselling Centre Malaysia

03-77855955 or 03-77810800

Life Line Association Malaysia

03-42657995

Cover image via BBC

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM