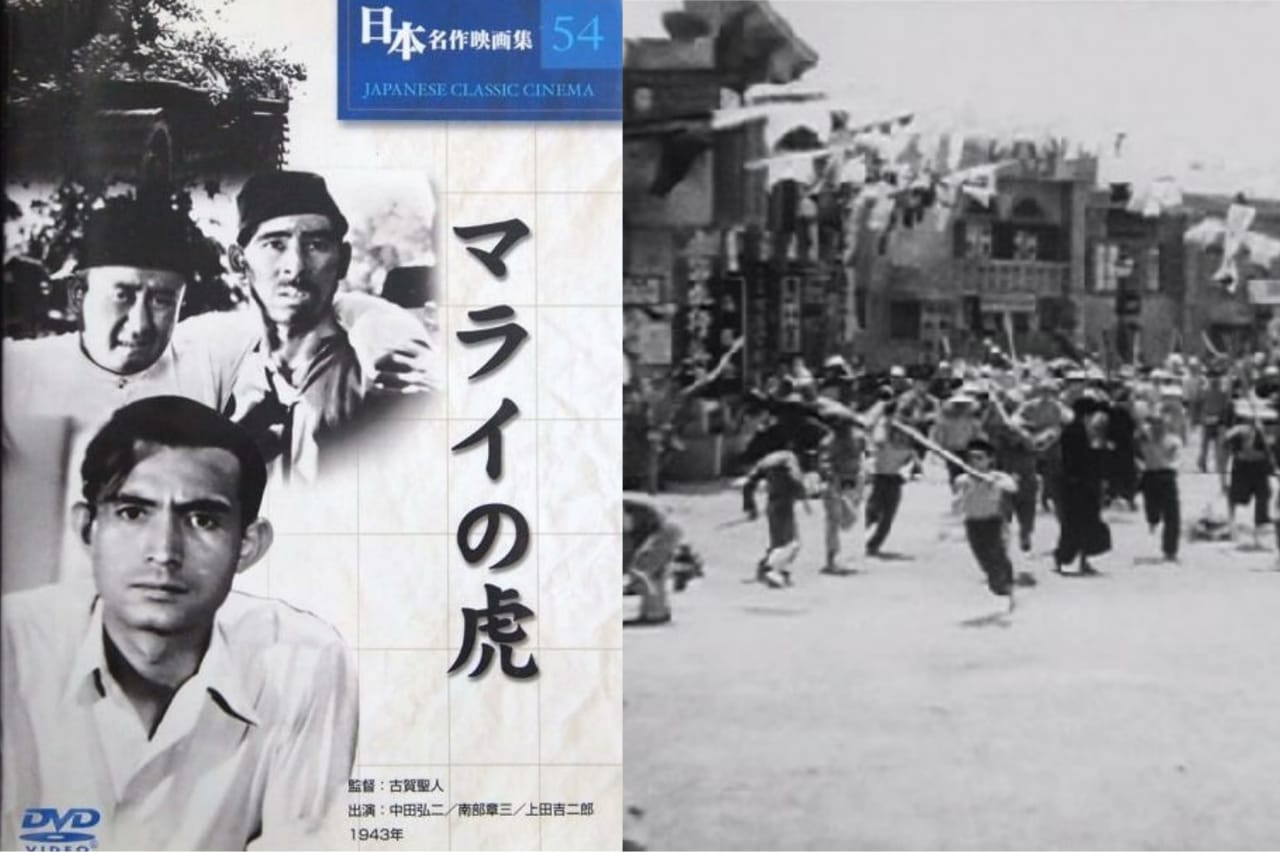

Lights, Camera, Propaganda: ‘Marai no Tora’ Chronicles Japan’s Strategic WW2 Twist On The Harimau Malaya Legacy

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

As the sun rises on the horizon of 31 August, we prepare to celebrate Merdeka, a day of pride and remembrance. Yet, beneath the veneer of valour and sacrifice that characterises the nation’s cinematic history, a different tale lurks – one meticulously designed through the lens of a Japanese propaganda machine, woven into the black-and-white frames of a 1943 film, Marai no Tora.

Where the tumult of physical battles subsides, a more insidious struggle unfolds; one for the hearts and minds of the populace. It’s a struggle where narratives and truths are deliberately twisted to serve a larger agenda. Released merely a year after Japan’s colonisation of Malaya, the movie stands as a striking example of how film was employed as a tool of manipulation during World War II.

For context, the aim was to secure Japan’s dominion over the economic riches of Southeast Asia, encompassing the Dutch East Indies, as well as the British territories of Malaya, Borneo, and Burma. A triumph in this endeavour would grant Japan economic autonomy within its empire while simultaneously displacing European influences from the East Asian region. The British-governed Malaya became a target, and from December 8, 1941, Japanese forces incrementally seized control, culminating in the capitulation of Allied forces at Singapore on February 16, 1942. The Japanese occupation endured until their surrender to the Allied forces in 1945.

A Calculated Campaign

Set against the backdrop of a tumultuous era, Marai no Tora (translating to “The Tiger of Malaya”, or as commonly quoted in Malaysian culture, “Harimau Malaya”) transports us to a time when borders shifted and allegiances were tested. Directed by Koga Masato, this war-time propaganda piece serves as a cinematic slice of history, weaving together the life of Tani Yutaka, a real-life Japanese who evolved into the legendary “Harimau,” taking up arms as a spy for the Japanese armed forces.

Derived from Wikipedia, on November 6, 1933, Tani’s sisters were brutally murdered in connection to the Mukden Incident. Seeking retribution, Tani transformed into “Harimau,” a local hero bandit who targeted Chinese gangs and British officers. Sharing his spoils with the needy, he was arrested, imprisoned for two months, and later became a secret agent for Japan during World War II.

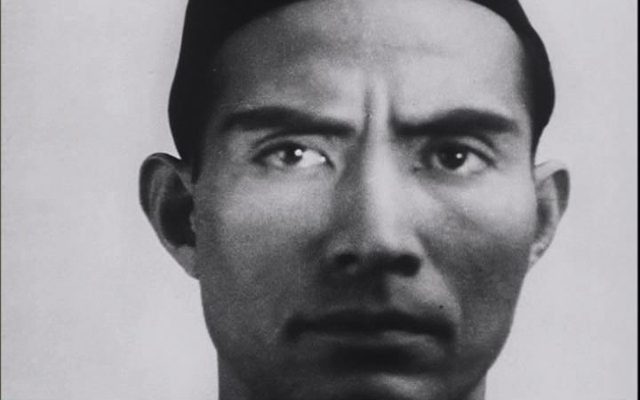

Influenced by local Malay friends, Tani Yutaka had embraced Islam and even married a Malay woman, albeit briefly. Notably, he’s depicted wearing traditional Malay attire throughout the film, emphasising his supposed connection to the culture. His journey ended in Singapore, buried with conflicting accounts of his demise and honoured at the Yasukuni Shrine.

The film, on the other hand, opens with tragedy – the anti-Japanese riots ignited by the invasion of northern China in 1931, whereby flames of unrest devour the innocence of Tani Yutaka’s world, as he is thrust into a maelstrom of revenge and survival. Koji Nakata’s portrayal of Tani Yutaka strategically invokes sympathy for a man allegedly pushed to extremes by grief and injustice.

Then, with the grace of a feline predator, Tani Yutaka embraces his newfound identity as “Harimau,” an outlaw who prowls the shadows, leading a band of Malayan guerillas. The film’s immersive journey takes us from the bustling streets of Malacca to the shores of Singapore, each location imbued with historical significance. Through a cinematic POV, we are transported to a bygone era, amplified by echoes of courage and despair.

With this, a tale of vengeance is embellished with heroic overtones, obscuring the fact that the film was carefully crafted to manipulate local sentiments and instead serve Japan’s colonialist agenda.

Colonial Shadows & Orchestrated Symbolism

The film’s cinematography is a journey in itself, an exploration of diverse landscapes that mirror the landscapes of the heart. From the bustling streets of Malacca to the tranquil shores of Singapore, each location becomes a character in its own right. As an audience, we traverse these places, our senses ignited by the visual and emotional resonance they evoke. In these moments, it feels as if we are tracing the very footsteps of Harimau, following his path through history.

In reality, the film’s imagery is a masterclass in propaganda manipulation, drawing on colonial grievances and orchestrating scenes for maximum emotional impact. Scenes featuring Harimau standing before British colonial buildings serve as powerful symbols—a Japanese man juxtaposed against the emblem of a distant empire. These visuals were meticulously chosen to fuel anti-colonial sentiments and ignite a sense of empowerment among the locals.

While the film employs historical events as a canvas, it eagerly blurs the lines between fact and fiction. Tani Yutaka’s purported “final mission” to sabotage a British-controlled river dam paints a vivid picture of his supposed fight against colonial oppression. This narrative, though, is another calculated distortion designed to evoke a sense of resistance and rally support for Japan’s wartime objectives.

The Theatrical Palette of “Marai no Tora”

As we delve into the intricate layers of the plot, it becomes evident that while reality may have paved the way, the film’s canvas is painted with the strokes of dramatisation. The protagonist, portrayed with earnestness by Nakata Koji, navigates a world rife with tragedy and treachery – A family shattered by the deeds of malevolent forces sets the stage for a transformation that transcends individuality.

We know that our lead character’s actions and sentiments are propelled by a desire for justice and vengeance. Yet, as the narrative unfurls, a distinct flavour of over-the-top theatricality emerges, tinged with a sense of near-amusement. The film’s portrayal of various nationalities is at times both captivating and exaggerated. Gangsters dressed as Chicago mobsters, a child’s life cruelly robbed, all play out against a backdrop that taints the plot with a heavy dose of theatricality.

Sonic Sentiments

At the surface, set against the backdrop of Tani Yutaka’s journey, the film seems to intricately melds its storytelling with the melodies of the past. Songs like ‘Terang Bulan’, in which Malaysian National Anthem ‘Negaraku’ finds its echoes are carefully woven into the film, a prime example of Japan’s multiple attempts at invoking a sense of unity between locals and the characters on-screen.

Another familiar tune that graces the film’s musical landscape is the melody of ‘Rasa Sayang Hey’, a song that resonates deep within the hearts of Malaysians.

Marai no Tora thus becomes not only a visual manipulation but also an auditory one, with songs that are strategically employed to evoke a sense of nostalgia and familiarity with its Malaysian audience.

Beyond Black and White

The legacy of “Harimau Malaya” echoes through time, but it is a legacy rooted in deceit rather than valour. Tani Yutaka’s transformation from an agent of vengeance to a tool of Japanese propaganda highlights the film’s true purpose. It serves as a chilling reminder of the power of cinema to distort truths, craft narratives, and manipulate emotions for political gain.

The myth of “Harimau” has persisted through the years, evolving into various forms in Japanese popular culture. From a heroic outlaw to a comic thief, Tani Yutaka’s legacy, extending from the film into various forms within Japanese popular culture. His memorial stone at the Japanese Cemetery Park in Singapore (pictured above) stands as a tangible link between history and remembrance.

The “Tiger of Malaya” title has other contenders, like Tengku Mahmood Mahyiddeen. While Tani Yutaka isn’t as widely recognised in Malaysia, he allegedly garners substantial respect in Japan.

As the curtain falls on Marai no Tora, it becomes evident that this cinematic creation is a reflection of calculated propaganda. The narrative serves as a vessel for Japan’s colonisation agenda, employing historical events as mere stepping stones to craft a manipulative tale. To reiterate, he film’s release within a year of Japan’s occupation of Malaya underscores its role in cementing the colonial narrative and rallying locals behind Japan’s cause.

In a world where history is painted with shades of grey, Marai no Tora stands as a stark reminder of the sinister potential of propaganda—revealing the depths to which storytelling can be exploited for ulterior motives.

Watching Marai no Tora is not merely an act of entertainment but an exploration of our collective history. It’s a reminder that even as propaganda distorts reality, it cannot fully erase the struggles, injustices, and complexities of the past. By engaging with this film, we can better understand the power of storytelling and its ability to shape perceptions.

While we acknowledge the propaganda at play, let us also recognise the human stories entangled within. Just as Marai no Tora was used to further political agendas, it also inadvertently documents the lives, emotions, and experiences of individuals caught in the whirlwind of history. In these moments, we find a resonance that transcends manipulation.

You can watch the full film via this Youtube link.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM