Camp Semangat: The Secret History of Malaysia’s Woodstock & War on Drugs

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

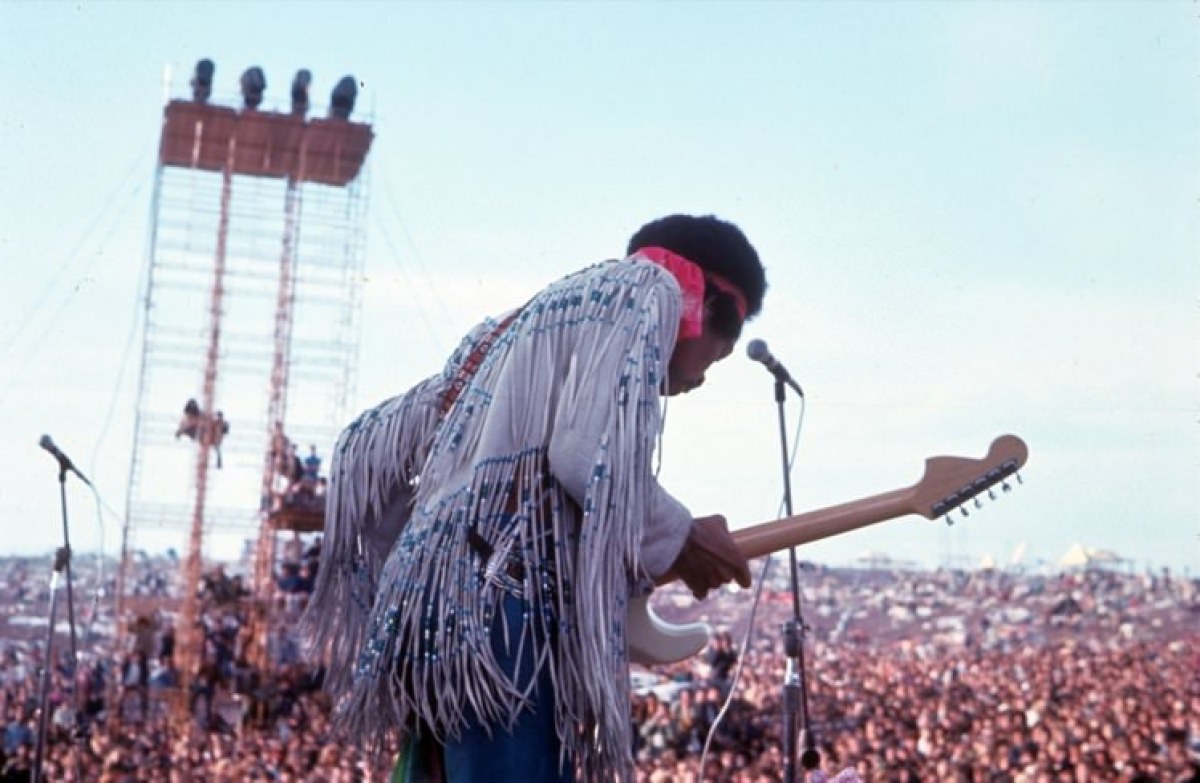

Every time we talk about Woodstock, what comes to mind are images of Jimi Hendrix playing the Star Spangled Banner onstage to a massive crowd of young people with a copious amount of drugs available.

The eponymous Woodstock festival was held at a dairy farm at Catskill Mountains, New York, south west of Woodstock (where the name comes from), with an estimated 1 million attendees from 15 to 18 August 1969, a figure that has yet to be rivalled by any music festival of today. It was a sign of the times–the youth fed up with conservatism and began questioning the powers that be who wanted to draft many young Americans into the army to fight the Vietnam War.

The Birth of Malaysia’s Woodstock

Woodstock arrived in Malaysia 3 years after the passing of Jimi Hendrix, and although it was not branded as a Woodstock-inspired festival, Camp Semangat certainly turned out to be like one.

Multiple Woodstock-ish concerts had already been organised across Malaysia following the actual Woodstock of ’69 in America. Hippie culture was beginning to trend in the East.

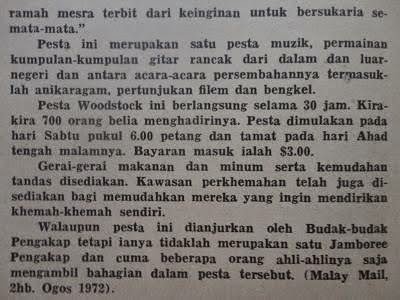

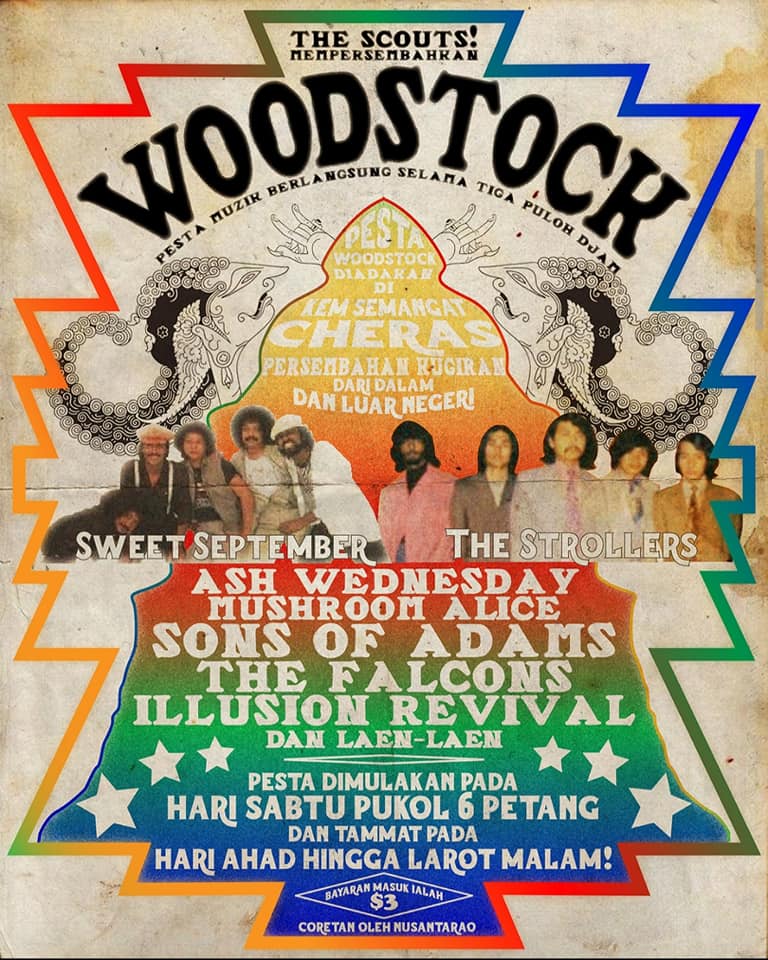

The most prominent Woodstock-ish concert was Camp Semangat held in July 1972, organised by the members of some of the bands performing and the Boy Scouts of Malaysia (Persatuan Pengakap) at Kem Semangat, Cheras.

It’s become an urban legend to the youth of today. You might have even heard it from someone–that their parents were hippies and engaged in some illegal revelry at Camp Semangat. It was certainly reported by the mainstream media as just that–a gathering of young, bad apples fuelled by drugs and Western culture.

The people who were there remember it differently though. This article was pieced together by comments on a Ricecooker article left by Charles Tyler (an organiser of Camp Semangat), Joe Rozario (an attendee), and research done by The Wknd and Cukong Press.

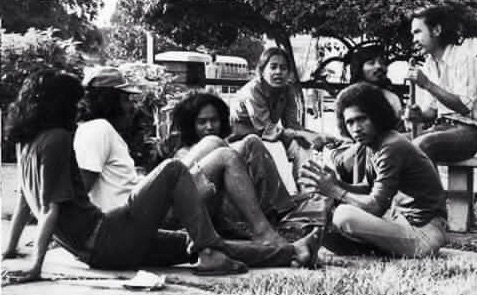

Unlike the hipsters of today who can’t even get to Good Vibes without Waze, the generation that went to Camp Semangat Woodstock were rebels. Joe Rozario, of the now-defunct Joe’s MAC vintage shop, was one of the attendees of Camp Semangat Woodstock, and his recollection of the event differs from what the media reported back then.

In a feature by The Wknd, he described the scene at the festival as “a new generation of people, you know, who refused to wear ties and follow the normal generation of the time, the older generation.” Hitchhiking down from Pangkor Island with his friend Raj, and they came to Cheras: “We had to stop at the 9th Mile and walk about two kilometres into the jungle. And there was this large group of people, of hippies, [at an event] organised by the Scouts! Imagine that!”

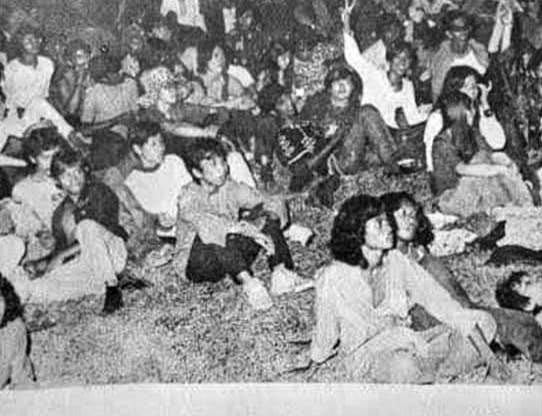

People came from Singapore, Johor, Malacca, Penang, Ipoh and even hitchhiked from nearby small towns to Cheras to witness the rock and roll fiesta but it’s unclear how many people attended the show. The Strait Times reported 500 while Malay Mail said 700, however those who were present claimed the reported number of attendees was just an attempt to play down the popularity of the event which could have had double or triple the amount of attendees.

The full list of bands (including those not officially advertised) that performed at the Camp Semangat Woodstock is probably lost, but we know for sure there were bands from Singapore, Indonesia and local bands like Sons of Adam and The Strollers–the latter dubbed as “one of the best psychedelic bands in Asia” in an article by local punk pioneer and music archiver Joe Kidd on his website The Ricecooker.

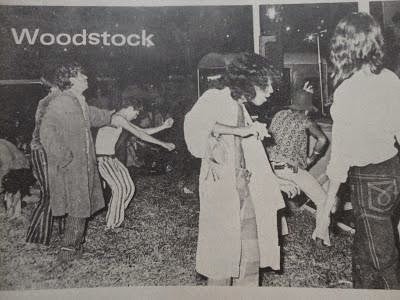

Rozario recalled one of the festival’s highlights was watching another local band, The Falcons who were from KL. “They turned up in a long trailer with big amplifiers – Marshall valve stacks – and Fender guitars, like Jimi Hendrix. Once they came, the whole area became wild. Before that, everyone had been sleeping; three days of music and a lot of grass led to people sleeping all over, waiting for this great event and when The Falcons came it was a burst of joy” Rozario explained. Rozario claimed it was an unbelievable set, everyone was happy for the next two hours or so and some people even tried to climb the the amplifiers. “It was a total knockout! By the time The Falcons finished the show, everybody was on their feet, clapping and dancing and singing.” Rozario also noted that in general, the festival was “a good time. Everybody was happy, it was just like a holiday in the forest. Every person there was your friend.”

So when do we get to hear about mom and dad sharing a joint, you say? As The Wknd‘s Azzief Khaliq wrote, the festival was done on a commercial level: “It’s important to point out that despite the hippy and counterculture associations of the term ‘Woodstock’, the festival seems to have been organised generally as an above-board, completely legal event: the stage was sponsored by Coca-Cola, which topped the stage with a—’ridiculously commercial’, in the words of one reporter—selamat datang signboard, and there were food and drinks stalls, film screenings, workshops and even stage shows, according to accounts from The Straits Times and The Malay Mail.”

One of the organisers of Camp Semangat, Charles Tyler has his own memory of that weekend. Apart co-organising the festival, Charles introduce some of bands and even recorded a song with local legends The Stroller. The Boys Scouts of Malaysia were billed as the official organisers, but according to sources, the idea and legwork was done by a group of expats who were friends with the performers and played music themselves.

Charles commented in the same Ricecooker article that, “There might have been a little grass smoked discreetly but as far as I could tell, all of the people who came were just average guys and gals.”

Charles claimed that it was “a nice event that a lot of people enjoyed… There was swinging and swaying and guitars playing and dancing in the fields – but it was all very nice and everybody was incredibly friendly and well-behaved.”

The event, as remembered by those who were there, was a peace-loving rock and roll show. There might be some weed being smoked (doesn’t that happen at all music festivals?) but it was an organised and legal event, even the stage was sponsored by Coca-Cola. So why did the mainstream media demonise Camp Semangat like it was a gejala sosial?

The Malaysian government had always considered rock music a serious threat, with or without drugs. Just looking at the statements made by politicians and policymakers months after the festival, point towards the government’s stand against rock music and their fear of the sweeping wave of Western liberalism.

Some reporters at the time seem to be playing the Devil’s advocate, with The Straits Times putting out headlines such as “Ban Long Hair by Royal Decree’ Call”, “Woodstock Show ‘A Plot To Weaken Youth” (an actual review of the Camp Semangat Woodstock festival), “Team to Probe Drug Taking at Scouts’ Festival” and so on.

The Straits Times reporter Ng Foo Ngok also wrote that the festival was quite a place for “potheads” and that marijuana was “smoked and offered openly”, and cheap weed was being sold openly over the weekend. Though the reporter was most likely writing to demonise the event, he noted that the crowd was “remarkably peaceful and friendly,” with “race and colour [having been] put aside.”

Rozario actually corroborated some of Ng’s claims. There was weed being smoked and there were dealers around, but Rozario remembers that there were other more-malicious drugs, namely “toon”- a black opium paste with sketchy origin, and heroin. The Wknd wrote that “The latter was apparently a drug of choice for some Westerners that attended the festival and there was some police trouble that came along with it.” Rozario recalled, “When the heroin came in, the police came. There were some raids on the third morning, if I’m not mistaken, because they caught some people taking drugs.”

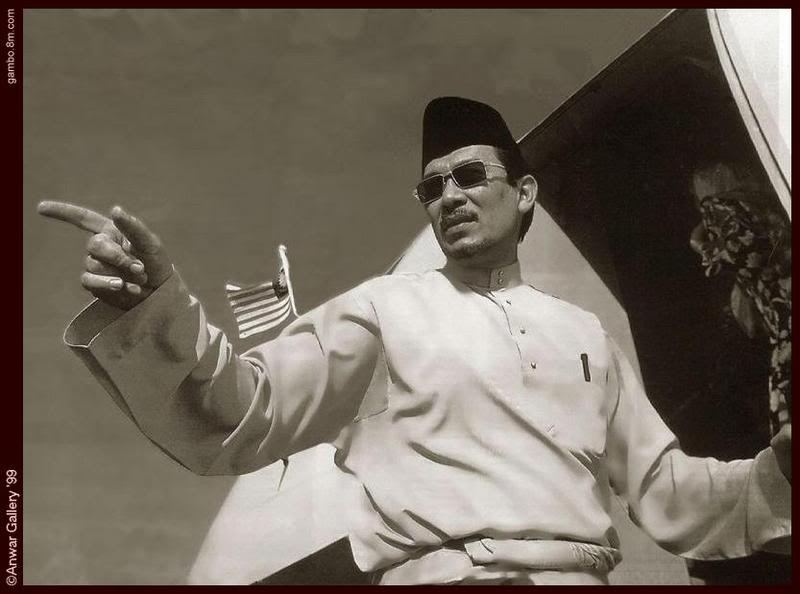

Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, who was president of the Malaysian Youth Council back in 1972, straight up put the blame on the organisers and fellow foreign concert-goers, claiming that it was the westerners that had influenced and led locals to rampant drug taking at the festival, going so far as to claim that the drug taking wouldn’t have happened had the festival been organised by locals since “they wouldn’t have allowed such a thing to happen because it is foreign to our way of life.”

And, in a depressingly familiar turn, he continued by pointing out that “certain people, mainly the English-educated, think it is all right because they have been influenced by Western beliefs. They think it is harmless. I must say it isn’t. We have our own way of life. Woodstocks are not in it.”

Camp Semangat Woodstock could have been the scapegoat event the Malaysian government was looking for to push their ‘War on Drugs’ agenda. The Wknd reported that there’s “a somewhat-popular notion that the term budaya kuning actually came into use due to Camp Semangat Woodstock and the belief, exemplified by what Anwar Ibrahim had to say above, that Caucasians had brought their immoral, drug-abusing ways to these fair shores.”

Charles commenting in the Ricecooker post, said, “the day after the festival the propaganda against it began. There must have been a government agent there taking pictures. The Straits Times ran a picture of just us Caucasians on the front page – with no locals at all in the picture – and we were about the only caucasians there, sitting on the grass in front of the stage together with the headline ‘Hippies Arrested at Drug Festival’. This was completely untrue! The picture itself was highly misleading. Nobody was arrested, nothing happened at all except music and good times. It didn’t even rain – no mud.”

Soon after the organisers went home after cleaning up the site, they learned that the police had visited and searched their apartments, leaving a notice of instructions to go and report themselves at their local police station. Nothing was found during the raid. Tyler said, “I think we were lucky they didn’t plant stuff and claim to find it. It could have been worse”. Nevertheless the organisers visas were cancelled, Tyler and the rest of Westerners who helped organised the event were given two weeks to leave the country.

Tyler recalled the irony, that “all the people I knew who helped put it on – Russ Vogel, from the Peace Corps, Kerstin Moller, a rotary exchange scholar, John Irvine, a helicopter pilot who worked for the oil industry, and myself – were the most clean-living, non-druggie types you could possibly find. Just look at the songs I was writing then! We all loved being in Malaysia and we did it for the local people as a public service. We certainly didn’t want to rub anyone up the wrong way and we were acutely aware that we had to keep it clean. The local Coca-Cola company sponsored the stage and we got permission from the Camp Semangat people to use the grounds. It was all as well-organised and wholesome as could be.”

Well, we guess some things never change. If politicians want to pick on random events or incidents that do not fit the norm of society, to gain political milage, they can and will, and in the case of Camp Semangat, have. It was the perfect opportunity to push a political agenda, to bring Malaysia deeper into Islamisation, and to blame Western culture if the youth did not follow through. Although the event was painted very negatively, those were there, who experienced the power of unity that music has, certainly felt differently about Camp Semangat, and have nothing but good memories out of it.

Unknowingly, the supporters of the anti-budaya kuning campaign that followed Camp Semangat were missing the real point in the government’s sudden decision to demonising the West…

The Vietnam War and The War on Drugs

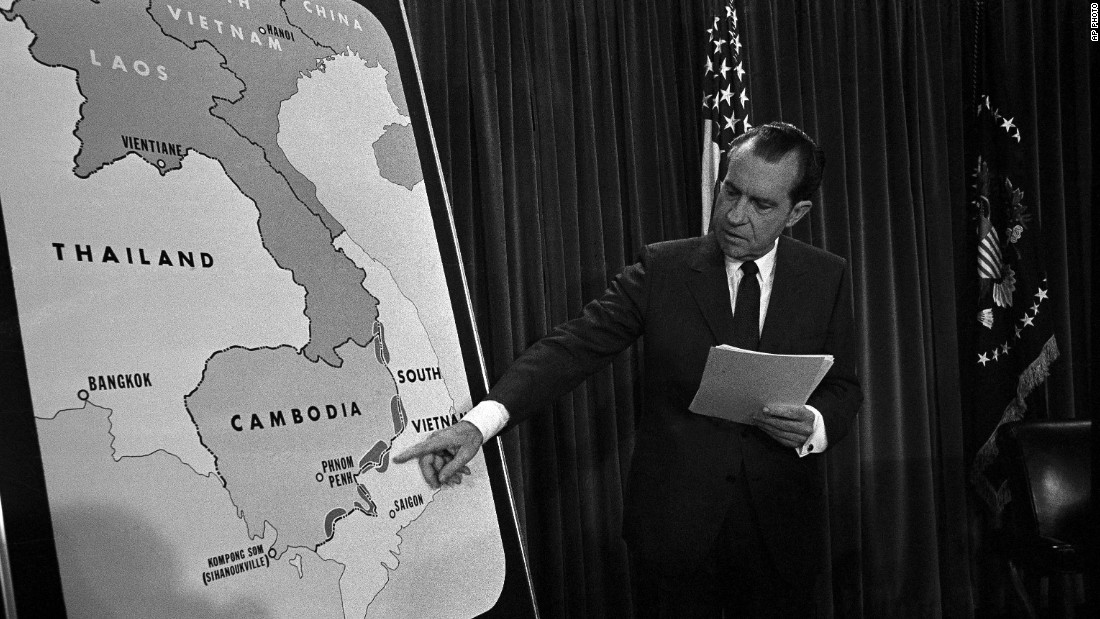

In America, Woodstock was the youth’s voice against the Vietnam War and their elected government. Opposition against the Nixon administration was going strong as Americans were getting fed up of supporting a war that had no end in sight. If you’ve seen Ken Burn’s Vietnam docu-series on Netflix, you’d know that America couldn’t even get out of it at this point because they had invested too much into the outcome of the Vietnam War. This led President Richard Nixon to ramp up his internal politics game by demonising the youth of America as drug-taking hippies and declaring the War on Drugs that targeted the black and hispanic communities, and reinforcing nightmarish visions of the threat of Communism’s spread. He could do this because he had the support of the ‘Moral Right’, the conservatives of America who were much alike the conservatives in Malaysia.

According to Cukong Press, in a Facebook post to promote their book on Malaysian urban myths, KL: Lagenda Urban Yang Digelapkan, the youth at that time in Malaysian universities and colleges were highly active in political discussion and activism. Not surprising, as they had not been jaded by that many years of bad governance and Malaysia was still considered a new nation, and more importantly, the ban on political activism in institutes of higher learning had not been imposed, yet. It was a time, hard to believe, when an 18 year old was considered an adult and students were expected to govern themselves on campuses to experience how democracy works in the real world. Campus grounds were like sovereign states ruled by student unions.

Among the issues being opposed by Malaysian college and uni kids was an agreement between Prime Minister Razak Hussein and Nixon. In their efforts to make South East Asia a ‘neutral zone’ (read: American), Nixon wanted permission to use Malaysia’s military bases in case Communism found its way into the region.

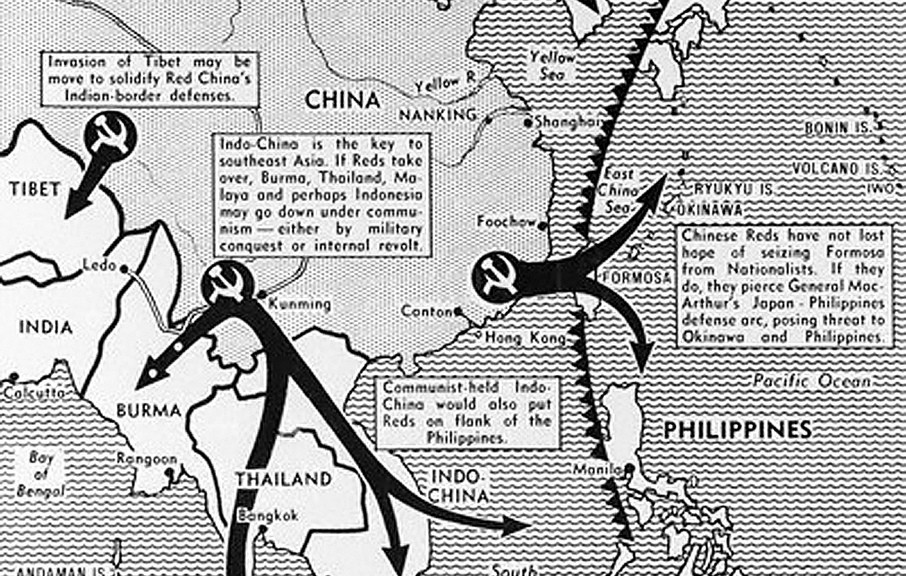

The Vietnam War went on but lawmakers in Washington were losing confidence. Nixon’s began efforts to set up defence bases in South East Asia to stop the influence of communism from spreading, or ‘The Domino Effect’ of Communism. He felt if this defences weren’t built, then Communism would surely find its way into South East Asia and America would have lost more than the war in Vietnam.

Nixon’s administration used a policy called ‘containment’–to contain communists in Indo-China–and started pouring big investments into Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia. Malaysia got its fair share of the pie but to enjoy it, our government had to play-ball with Nixon, despite opposition on his policies by young Malaysians and young Americans alike.

During this period, the Razak administration tried to get on Nixon’s good side by making sure youth-rallying events like Camp Semangat Woodstock didn’t happen. PEMADAM (Persatuan Mencegah Dadah Malaysia), an anti-drug NGO was formed while Nixon was already raging his War on Drugs on the counterculture scene, and secretly on American minorities. This is also when weed popularly became misclassified as a Class A drug.

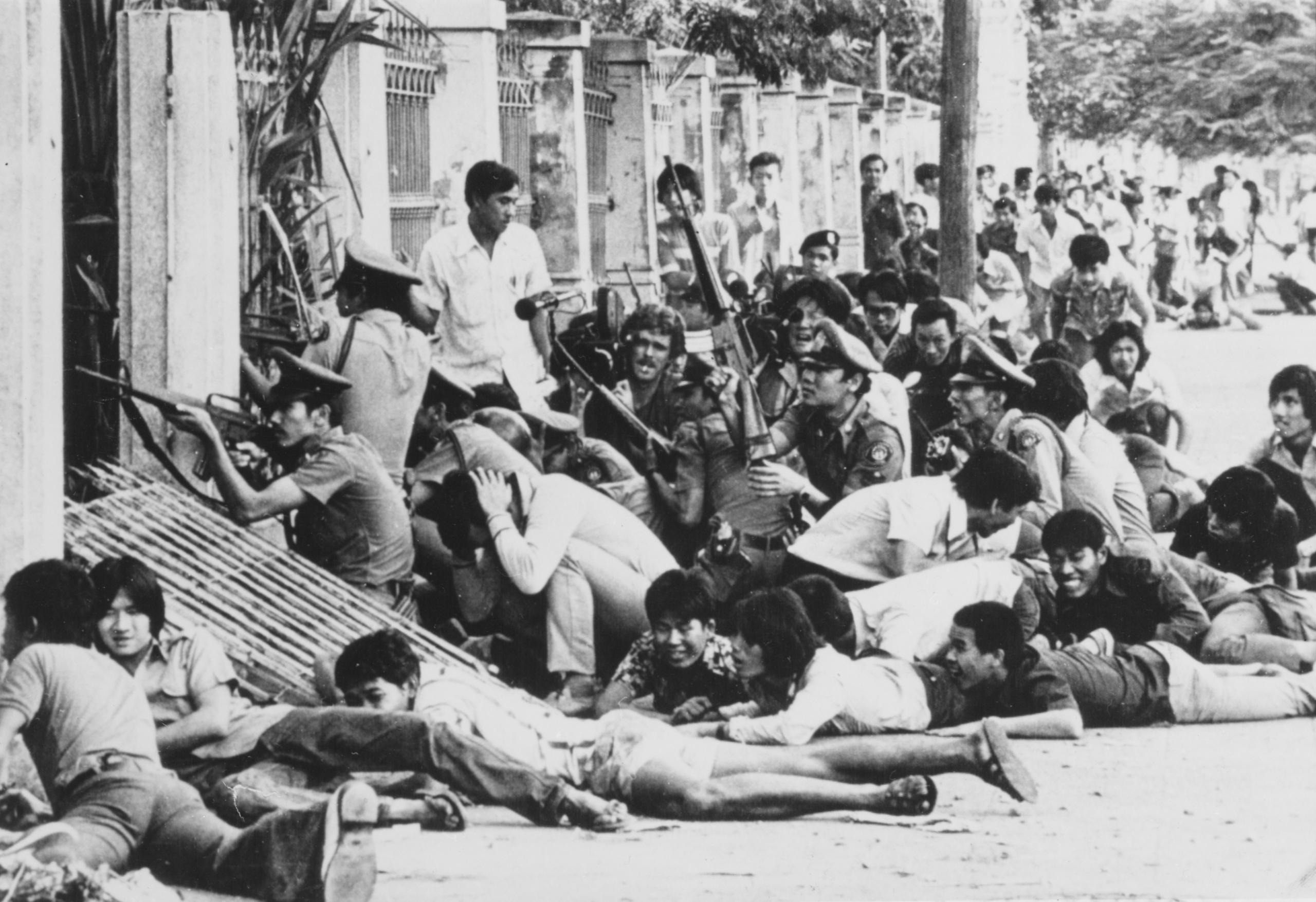

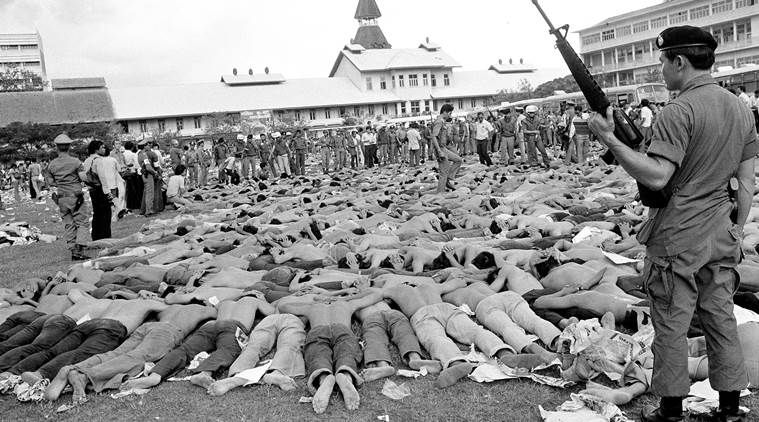

In October, 1976, a year after the Vietnam War ended, Thammasat University in Bangkok was occupied by leftist students demonstrated against Thailand’s former dictator, Thanom Kittikachorn from returning to Thailand. Protestors were labelled as communists and were beaten, raped and killed in a brutal massacre.

A year before this happened, sensing the potential threat of student-led takeovers of campuses, the Malaysian government amended the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971. Education Minister at that time, Mahathir Mohamad signed off on the amendment which covered all public higher learning institutions, to prevent university students from marching and protesting against the government, as well as to maintain nationalism among the sheepeople of the country. The Act was amended once again in 1995 – when Mahathir Mohamad was Prime Minister. In 1996, Mahathir amended the act again to include all private higher education institutions in the ban on political activism as well.

Despite conservatives who still criticise Woodstock concertgoers as those who ran away from the war or supported deserters, Woodstock in America has gone down in history as the mother of all modern, peace-loving festivals. The site of the festival is even listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In Malaysia, Camp Semangat Woodstock is still a relatively untold story, with half-truths surrounding that particular weekend of peace and music.

We may never know the full story, or what really happened, but we sure know that the hating on youth culture and nonconformism has never stopped. Here’s to the flower children of the past, present and future… rock on.

This story was translated from Cukong Press, with added information from a feature from The Wknd, and comments left by organiser Charles Tyler on an article on The Ricecooker.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM