Ambitious To A Fault, ‘Spilt Gravy On Rice’ Is A Bold Film That’s Sadly 11 Years Too Late

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Malaysian cinema and theatres have made major strides within the past few years.

Films that used to be deemed too controversial for the public eye have since seen theatrical releases due to the loosening of our censorship board and the blossoming of Malaysian perspectives.

While some films have yet to be embraced by the mainstream audience despite its astounding quality and narrative (read: Mentega Terbang), one particular film, Spilt Gravy on Rice, which was intended for audiences 11 years ago, has finally broken through the ether after being rejected by FINAS despite their many rewrites and resubmissions.

Best Costume Designer ✅

Best Production Design ✅

Best Editing ✅

Best Screenplay ✅

Best Newcomer Director ✅

Best Supporting Actress ✅

Best Film ✅Alhamdulillah 🤲🏾#FFM32#LensaFFM#FilemKitaCitraKita #FestivalFilemMalaysia#SpiltGravyOnRice #SpiltGravy pic.twitter.com/AKiot36iwE

— Spilt Gravy on Rice (@SpiltGravy) December 3, 2022

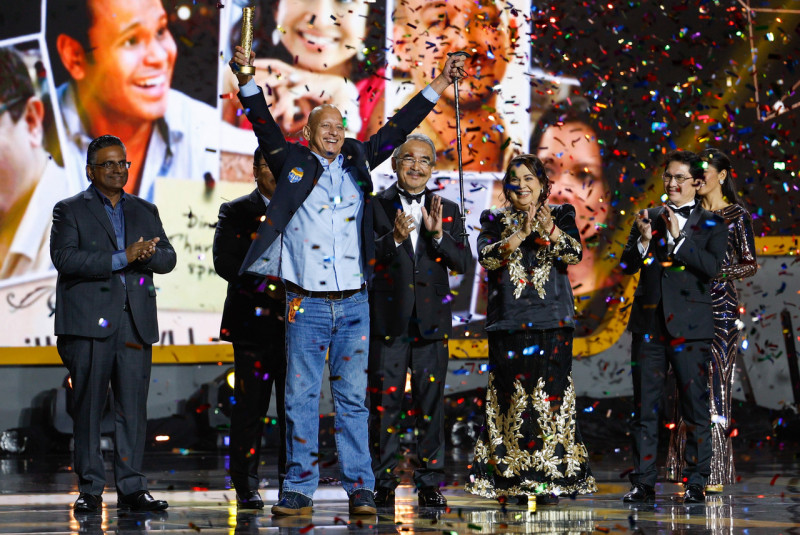

Currently available to stream on Netflix, this film made waves on social media and even won 7 awards at the 32nd Festival Filem Malaysia (FFM), including the coveted Best Film accolade.

Naturally, as an avid supporter of the Malaysian film industry, I watched Spilt Gravy on Rice on Netflix and I completely understand why the community was pushing for its theatrical release for over a decade.

However, watching it in today’s climate, I can’t help but notice its apparent flaws that are made worse with age.

Without further ado, here is my honest review of Spilt Gravy on Rice.

P.S: I urge you to take my opinion with a grain of salt and to make your own judgments.

What is Spilt Gravy on Rice about?

Originally adapted from a beloved play of the same name, Spilt Gravy on Rice, to the naked eye, is a film about the isolated inner turmoils of a pseudo-liberal, T20 family, but if you take hold of the lens and zoom in, you’ll notice that it is essentially about humanity.

Told in vignettes that gradually begin to assemble like pieces of a puzzle, the film focuses on the 5 children of a wealthy journalist who is reaching the tail end of his hedonistic, glamorous life.

Each child has a different mother and is vastly different from the next.

Zak, the first born, is a drug addict and drug pusher who is often seen borrowing money from his siblings to feed his growing addictions and aberrant lifestyle.

Husni, the successful one, is a closeted homosexual who, throughout the movie, is battling his sexuality by “not wanting to be gay anymore” but somehow always falling back on his word.

Darwis, the average straight-cut Joe, is an English lecturer who has lived a superbly uneventful life when compared to his siblings, so he feels the need to be joined at the hip to his father – almost as if he is trying to absorb his accomplishments through osmosis and make them his own.

Kalsom, the fiery feminist, is a playwright who is obsessed with retelling Malaysian history through the eyes of the marginalised, but instead of platforming the voices of minorities, she speaks over them, muting their actual, lived experiences.

Finally, we have Zai, the trophy wife and absent mother who lived her entire life as someone’s something (wife to a successful businessman, daughter to an acclaimed journalist, mother to a budding prodigy) to the point where she has no idea who she is if she simply stood on her own two feet.

The film is a Pulp Fiction-esque odyssey that follows the textured lives of each individual before finally coming to a head in its third act where they confront the patriarch, Bapak, and how his experiences inadvertently shaped their own.

As aptly summarised in the film’s tagline, Ke mana tumpahnya kuah kalau tidak ke nasi…

Why does Spilt Gravy on Rice feel bloated and dated?

The film clocks in at 1 hour and 55 minutes but after my initial watch, I felt like I had undergone several different lifetimes in succession.

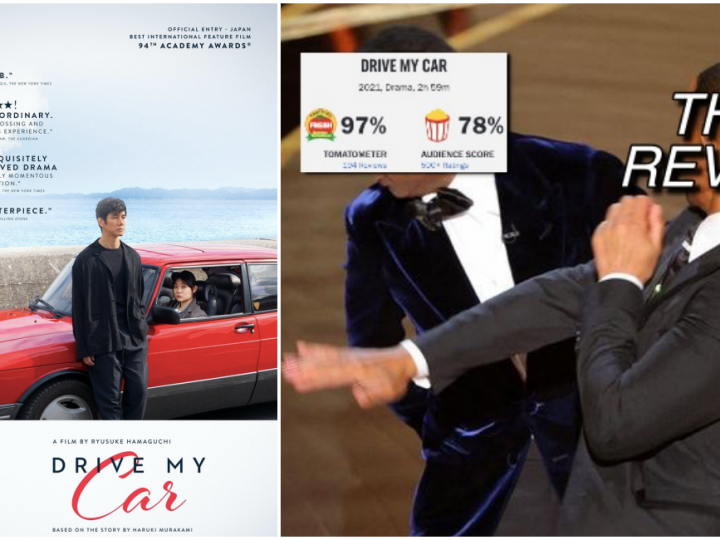

I am no stranger to films that run for even longer than 3 hours, so I was surprised to feel the painful crawl of Spilt Gravy on Rice despite it being relatively fast-paced and short in duration.

After digesting the film, I realised that I felt this way because the film played out more like a laundry list than it did an actual feature film.

11 years ago, the topics injected into Spilt Gravy on Rice were usually discussed in hushed voices and secluded rooms.

Themes of sexual violence, homosexuality, drug addiction, feminism and the barbaric racial tension of our country were not things we could enlarge and portray on the big screen, which is why I commend this film for being bold enough to push the threshold and flip off the censors.

But when you touch on topics like these, they should be handled with grace and care – not used as talking points to flesh out characters and paint a morbid picture of our repressed country.

Because the filmmakers wanted to tick every box on their list, they forgot that they needed to address these issues, not simply acknowledge that they exist.

In the final act of the film, which in my opinion shows the filmmakers going off the rails, all of these issues are discussed all at once in what feels like a muddled conversation over topics that should be handled with clarity.

The climax was irreverent and acted in a way that felt like sitting through a high-school comedic improv show, which arguably isn’t the best way to tackle subjects like sexual violence and LGBT acceptance.

Despite being intended as a heartfelt resolution to a tumultuous familial feud, the final scenes manifested a cacophony of unsolved traumas sugarcoated by tritely convenient remarks made by Bapak to absolve him of being a negligent father.

In actuality, Bapak is arguably the antagonist of the film and the filmmakers’ attempt at redeeming him towards the end was futile in my eyes.

Apart from his negligence, his role as a husband to 4 wives (and 2 mistresses) also leaves much to be desired.

Treating the mothers of his children like trinkets on a mantel to wax nostalgic – as if they solely existed for his pleasure and pride – his anti-feminist behaviour even trickled down to his children, most notably Kalsom.

Brazen in her disdain towards her mother’s “unremarkable” life because of the apathy she showed when her husband took multiple wives, she dedicated all of her plays to Bapak, the source of their strained relationship, not realising that he is the one to blame for it.

Despite all of the problematic elements I have mentioned above, I do not blame the filmmaker for attempting this 11 years ago because repression usually leads to overindulgence.

But now, it’s clear that a story with a narrower focus that doesn’t succumb to gluttony would definitely platform these issues in a more deserving way.

Take for example the Linklater film, Waking Life, which is essentially a compilation of conversations about philosophy, lucid dreaming and mortality rotoscoped into a feature film.

Its non-linear storytelling that encompasses relatively heavy topics felt coherent by the end of the film due to the director’s focus on highlighting every conversation – making sure the message is heard loud and clear.

Spilt Gravy on Rice feels like too many people talking all at once and for a film with so much substance, in the end, it felt tragically unsubstantial.

While this may have been pivotal 11 years ago, today, we can find many other films that do the same thing – and better.

In hindsight, to completely fault the film (or its filmmakers) for its flaws would be unjust, especially when we remind ourselves that times were different over a decade ago.

So despite the improvements that could have been made to the film, I still have resounding respect for Spilt Gravy on Rice because it was brave enough to do what it did at the time, motivating more filmmakers to chase the evergreen pursuit for a more outspoken Malaysia.

We at JUICE look back fondly on Spilt Gravy on Rice, accepting its flaws whilst thanking it for birthing new generations of playwrights and filmmakers who not only dare to create, but also dare to innovate.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM