Tokyo Idols Uncovers the Urban Loneliness Surrounding Life in Modern Japan

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

Thirsty for JUICE content? Quench your cravings on our Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp

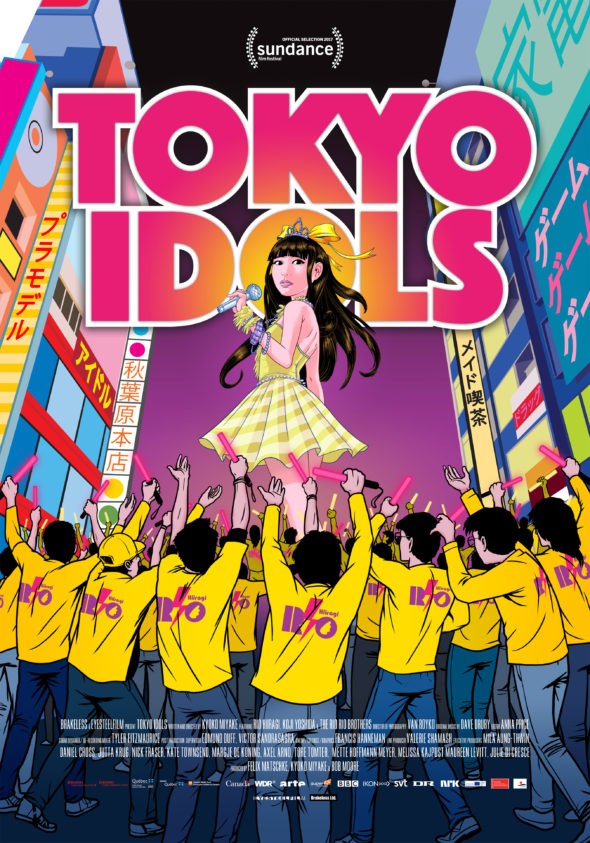

Tokyo is home to more than just a few mind-boggling services that have cropped up as replacements for real-life relationships. From cuddle cafes to rent-a-boyfriend amenities, each of these represent more than just mere novelty subcultures; they’re symptoms of a social phenomenon where the advancement of technology and the internet is removing the need for human intimacy. In what is quickly becoming a post-futuristic society, Kyoko Miyake’s documentary, Tokyo Idols, examines the city’s idol culture and the middle-aged fans who invest their whole lives in young girls who sing, dance, and embody an ever-narrowing ideal of Japanese femininity. With the plethora of films that have documented the ins-and-outs of otaku culture, I went into the screening of the film at this year’s Cooler Lumpur Festival hoping that it would show a new side to the issue that curious observers weren’t already aware of.

Far from being a sensationalised piece akin to the work from Vice (like Boyfriends for Hire in Japan and Single Japanese Women Are Buying the Boyfriend Experience) concerning similar topics, Tokyo Idols is at once inquisitive and self-reflective on the perplexing nature of idol fandom and the ways in which it distinguishes itself from the kinds of pop stardom one might find in America or Europe. Rather than having the voice of a host (most likely from a Western background) dominating the narrative, the story is carried forward by the actual inhabitants of the Japanese idol ecosystem: Rio, a budding young starlet, and her loyal fans, aged from 35 to 50 years old and known affectionately as the ‘Rio Brothers’, are at the centre of the film. The camera follows them through their lives as they go through concerts, fan meetings, and the lull of everyday routine in the city together.

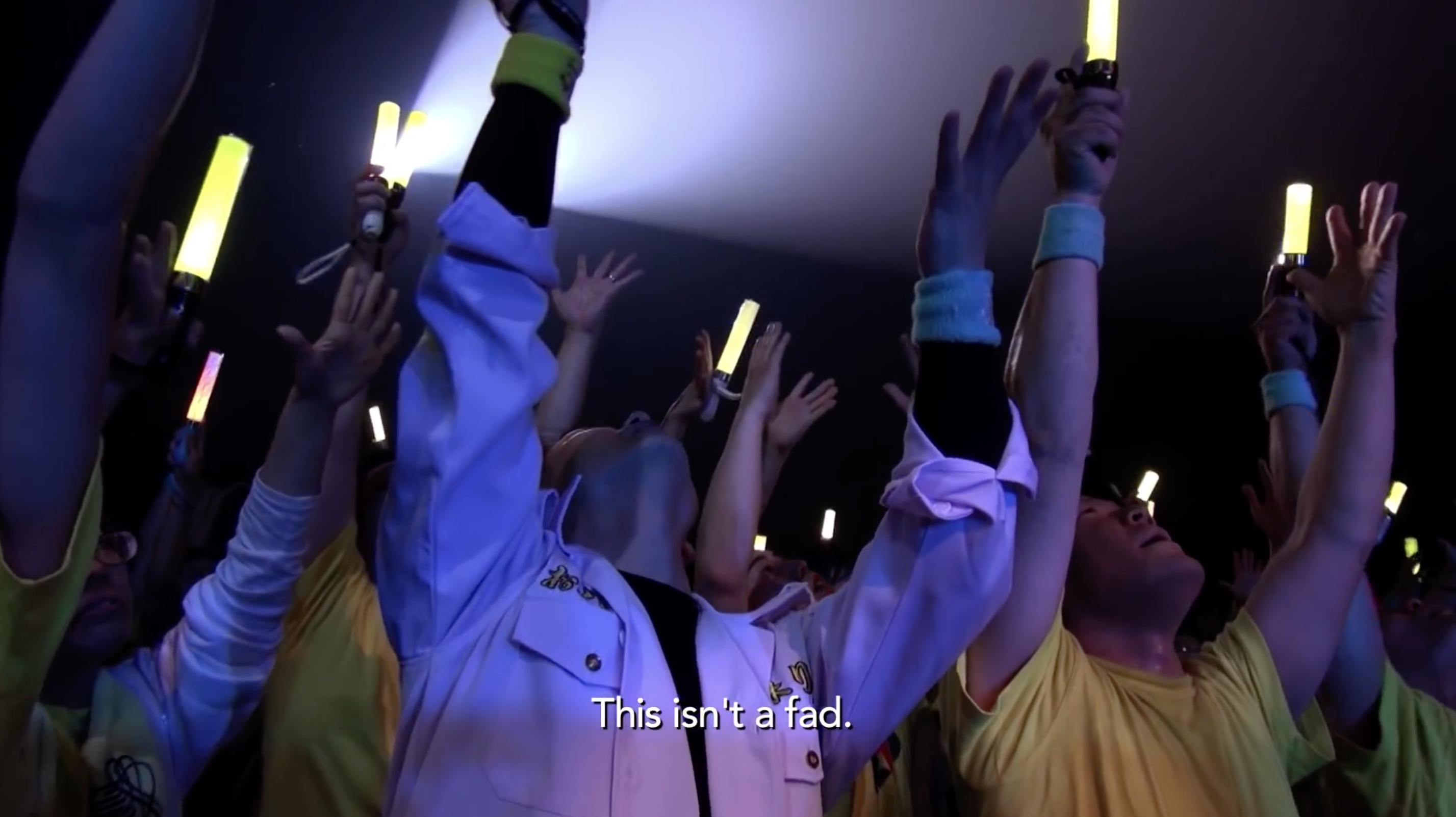

Miyake’s film presents the relationship between idol and fan as a symbiotic one; after choosing to become an idol as a gateway to becoming a serious artiste, Rio’s career is kept afloat by exposure and patronage from her fans, while her fanbase derive much of their life’s purpose from ardently following the progress of their favourite idol. In an interview with fans, many of them state that besides their commitment to attending concerts, going to fan meetings, and purchasing merchandise, their life is mostly monotonous and isolating. None of these middleaged men see a reason to seek female attention elsewhere other than interacting with idols at fan meetings and handshake events. The co-dependent relationship between these young women and their fans explains the longevity and profitability of such an industry in Japan, but the film also makes us painfully aware of the superficiality of idol-fan relationships. Much of it is based in materialism and shallow interactions that don’t last for more than a few minutes, and I was left wondering if the devotion these older men showed was a veiled addiction, morphed from the kind of hysteria that would often plague teenagers and their worship of boybands and girl groups. Why had it specifically afflicted men who were far beyond young adulthood, and what appeal did the image of these idol girls nearly half their age hold for them?

Tokyo Idols juxtaposes scenes of glittering pop concerts with tranquil, often lonely shots of idol fans living their daily lives. They walk the streets among the throng of city dwellers, their bright fandom apparel being the only marker that helps them stand out from the monotonous colour palette of working people in the metropolis. The stark contrast is a painful reminder of the loneliness at the heart of city life. The downtrodden backstory that most of these middleaged fans possess is a testament to the trauma left on modern Japanese masculinity ever since the bubble burst of the economy in the ’90s. Many salarymen turned their backs on typically masculine corporate rules as a result, sparking both economic disillusionment and a complication of gender roles between males and females. Many men were averse to the growing autonomy that women were gaining and likewise, many women were dissatisfied with the passive nature of Japanese men and their preferences for 2D women over real-life relationships.

The film doesn’t adopt a harsh or critical tone like that of Antoine Lassaigne’s Love and Sex in Japan, which featured interviews with government officials to try and confront the problem of the nation’s declining birth rates, but it is aware of the growing disconnect that idol culture has forged between the sexes and the warped context of what it means to fit the female ideal in Japan today. As technology advances in line with the rise of female pop idols, the construction of the ideal woman is growing to be more and more distant from real-life women who, in recent years, have begun to step away from traditional modes of being and gained more financial independence from their male counterparts. In this environment of changing gender roles, idol culture has become a sort of ‘safe space’ for men to seek refuge in, where the overly-cutesy, hyperfeminine, and undeniably juvenile image that idol girls present would pose little to no challenge to masculinity.

Perhaps the most enlightening and by far the most bizarre phenomenon seen in Tokyo Idols was the existence of idol groups with members aged as young as 10. These child idol groups are groomed for the very same fanbase that their older teenage counterparts cater for: middleaged men. When interviewed, fans of the group said that they viewed the girls as ‘friends’, or that they wanted to be seen as brothers to them. Granted that these men are not showing up to gigs trying to grope or harass these girls (fan meetings are always respectful of both parties’ personal space), but the existence of such a relationship shows, if anything, the widest gulf between men and women in the film, one where men would rather indulge themselves in pseudo-paedophilic relationships than pursue the attention of any female above the legal age. One journalist in the film stated that Japanese society would “do whatever it takes to protect the fantasies of men,” and the presence of underage girls as young as 10 dancing and singing to crowds of cheering salarymen was a clear testament to that.

There’s a lot more to the isolating nature of idol culture than the industry itself; Miyake’s film gives voice to the wounds that lie deeper beneath the surface, ones that are inflicted by warped expectations of men and women and the suffocating nature of evolving gender dynamics in a hypermodern society. Even if idol culture were to evaporate tomorrow, the disconnect between men and women would be as rife as ever, and it wouldn’t be long before another subculture would pop up to fill in that void.

Unlike other filmmakers that have documented similar phenomena (such as host clubs, cuddle cafes, and the pornography industry), director Kyoko Miyake grew up in Japan, and Tokyo Idols comes from a place where she confronts her own stance on womanhood and Japanese society’s constraints around gender expectations. As a result, the film doesn’t seek to shoehorn Japan into being the bizarre Other, but instead it meditates on the complex relationships between men and women in her birth country, endowing the issue with the voice, dignity, and attention that it deserves.

Tokyo Idols was screened on 17 August ’17 as part of the Cooler Lumpur Festival 2017: Notes from the Future.

Read up on the history of the dating simulator, whose genesis can be traced back to (you guessed it) Japan.

Get Audio+

Get Audio+ Hot FM

Hot FM Kool 101

Kool 101 Eight FM

Eight FM Fly FM

Fly FM Molek FM

Molek FM